Your donations help T1Determined #keepgoing.

The No Wake Zone: Why Endurance Swims Are Challenging—and Scary—for T1D Athletes

“Now I lay me down to sleep. I pray to God I hear that beep,

But if I die before I wake, I’ll know what dosage not to take.”

— The Type 1 Diabetic’s Prayer

Can you spot the two swimmers with Type 1 diabetes in this picture?

You can’t usually tell unless you happen to spot a CGM (continuous glucose monitor) sensor or Omnipod insulin pump on somebody’s body, or can see an insulin pump in an Aquapak. Sometimes those are hidden under swimsuits to keep medical equipment from detaching and floating off.

But endurance swimmers with Type 1 Diabetes have more to worry about than just losing a $300 transmitter in the water or staying inside the “no wake zone” where fast boats aren’t supposed to be.

Swimming burns calories…but how many?

Swimming is excellent exercise, for sure. Type 1 diabetic swimmers, however, need to know how many carbs they’ll burn through in a given period of time.

That’s something you learn only from practice, and it means that if you don’t want to risk a low blood sugar while you’re out in the water, you test a lot at the pool to get an idea of how fast you use up a given amount of fuel, and whether it’s a “slow burn” from a long, relaxed swim or a “rocket burn” from swimming your fastest pace.

The first thing you need to do before you hit the open water is to find out what your fueling needs are and what distance everyone’s going, as close to accurate as you can get.

It’s one thing for your sports nutritionist or dietician or whoever to tell you you need X amount of water, X amount of carbs, X amount of fat, etc., per fuel break at X interval of time.

My non-diabetic friends, it’s not going to kill you if you miss-estimate distance or skip a feed.

It could quite possibly kill one of us.

Swimming uses more fuel per unit time than other sports

If you’re used to taking on 30g of carbs every hour on a long run, count on taking on more like 60g per hour on a long swim, unless it’s a really relaxed affair or your form is so efficient that you burn the fewest amount of calories possible for the distance.

After all, you’re working your whole body: arms, shoulders, back, core, and legs. Everything is doing work. You’re not just locomoting, you’re literally crawling through a thick, buoyant liquid that pushes back on you. It’s sustained resistance training, so in a sense it’s both aerobic and resistance training.

Normally that’s good, but not if your blood sugar tends to drop quickly from exercise.

Fueling needs may vary based on conditions

If you’re swimming in choppy water, against waves, tides or current, or in other physically challenging environments like wind, the same distance can be considerably harder to swim. You’ll make greater effort and burn more calories in less time.

If you normally plan on getting a glucose gel when you get back to shore to start the next loop, you may need that glucose gel before you get to shore.

To that end, I always tuck a couple of 25g-carb UnTapped maple syrup packets under the edge of my jammers so I can treat a low blood sugar on the spot rather than have to try to swim 200 meters back to shore with a BG of 56 mg/dl.

To disconnect or not to disconnect, that is the question

Some T1Ds I know disconnect from their insulin pumps while they swim. And up to a point, this works. For a 1-mile swim, for instance, you’re disconnected for as little as 30 minutes and no more than an hour, unless you’re a very fast or very slow swimmer.

But that doesn’t work once you go longer.

I’ve heard stories from quite a few of the 300+ diabetic ultra endurance athletes who have completed full 140.6 Ironmans about disconnecting from their pumps before the swim—only to discover that the swim start was delayed, or the gels they ate started kicking in early, or their BG’s running high due to race jitters, or they really needed at least a small bolus to cover the two hours they’re in the water.

They start the bike portion of the race around 350 mg/dl, cramping and energy-starved despite having fueled adequately.

And I’ve heard plenty of scary stories about bolusing before the swim and going low in the water as a result.

Some, like me, choose a waterproof insulin pump. The old Animas Vibe was great for that. The Medtronic 670g is also IPX8 waterproof but has its own issues with CGM integration, calibration inconvenience and sensor accuracy. The Tandem t:slim X2 is only IPX7 water-resistant and pressure sensors inside the cartridge chamber will cause it to report an altitude error if the air intake valves are blocked by water for too long. The Omnipod is IPX8 waterproof but somewhat at risk of detaching if the adhesive is soaked for too long; and moreover, the controller that allows you to bolus for that “stress high” before the Big Race isn’t waterproof at all.

I wear an older Aquapak, the one that they used to make for people who wanted to put their iPods in a waterproof bag and listen to tunes on waterproof earbuds or headphones. My Tandem t:slim is about the same size as the old iPod and the infuser tubing fits through the gasket for the headphone wire. The Aquapak still admits water, but only a teaspoon or so. A folded paper towel tucked into the Aquapak absorbs enough water to keep a pocket of air around the pump to equalize pressure at the air inlet valve. It’s a janky arrangement that produces a small amount of drag, but it works for my longer swims of about 6 miles.

Some people just go “off pump” for the day, inject a long-acting insulin such as Lantus, and skip the pump entirely.

I haven’t experimented with this method yet, but it’s part of my Key West training plan.

The obvious downside is that an injection commits you to that basal insulin dosage for the entire day, and if you’re prone to going low after a workout, well…I’m reminded of the words of Jethro Tull’s song “Locomotive Breath”:

“the train, it won’t stop going; no way to slow down.“

Endurance swims can make it challenging to get fuel and electrolytes

For most marathon swim events (generally, anything over 6 miles/10 kilometers), you’re not allowed to touch your support vessel for any reason. So fueling breaks AKA “feedings” generally consist of having your kayaker toss you a bottle about half full of liquid into the water on the end of a polypropylene rope. The bottle can’t be too full or it sinks, and the rope will sink if it’s nylon or paracord.

If you’re really badass, you can manage to do this will sidestroking or some other forward movement. But it can be a challenge to drink while swimming.

Your other option is to drink your nutrition from the bottle while treading water or floating on your back. Carbs, protein, fat—it all goes down as liquid unless you are really good at eating peanut butter sandwiches out of a Tupperware box while treading water. Most of the time, you’re slurping it down and trying not to waterboard yourself. Speaking solely for myself, that happens sometimes and I end up burping and coughing some of it out. So much for taking in exact quantities of anything.

Sometimes the water is choppy and conditions aren’t that great for feeding, so you push it a little later or look for chances to feed early. Sometimes good times for feeds never come, and you get in a little gulp of nutrition when you can. That’s one more reason I’m actually pretty superstitious about not heading out without several UnTappeds tucked under the leg of my jammers.

Little oversights and delays can lead to your not getting enough food or liquids. You don’t get enough carbs, and the carbs you do get don’t absorb as quickly due to dehydration.

If you’re trying to pull off a long distance swim with Type 1, you can’t overlook the little stuff, because it becomes big stuff pretty quickly.

Endurance exercise can make you dangerously insulin sensitive

During a long swim (or any other form of endurance exercise), a lot of muscles are screaming for glucose, and if you have any insulin on board, they’re fighting against your liver to replenish glycogen. Chances are good if you were just tooling along and then put on a burst of speed to beat the clock, another swimmer, or the tides, you’ve probably already dumped and burned whatever glycogen stores you had. You bonk, you go low, and suddenly everything seems like a meaningless struggle.

You get out of the water. You feel great—a little wobbly, maybe. But your time wasn’t bad. You chow down like a horse. You don’t even bolus for dinner. And despite all that food, your blood sugar crashes hard while you sleep.

Insulin helps you store energy—in muscles, in your liver, and in body fat. When you’ve had a long, hard aerobic workout, you actually need energy available to rebuild things like broken down muscle and replenish glycogen. You don’t need to store as much of the energy from food, and that’s why insulin production in non-diabetic people drops when they’re physically active. For us, it’s more of a stick-shift than an automatic.

Get stuck in the wrong gear (too much insulin) and not enough glucose is left in the bloodstream to power the brain.

Oops.

If you’ve read my blog post about a dangerous low I experienced in Odessa during my run across Texas, you know how scary those moments can be.

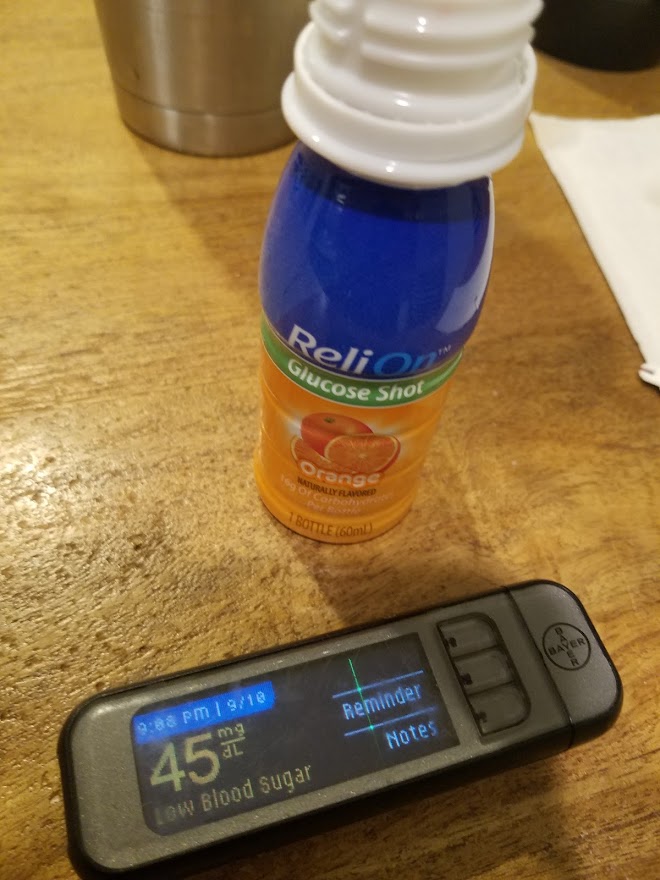

The image below was taken about an hour after I got back from a 5-mile swim in mild chop and ate a light supper with no extra insulin bolus.

For those of you who aren’t Type 1 Diabetics, 100 mg/dl is normal. below 70 is considered a mildly low blood sugar but not an emergency. Below 50, your thinking’s impaired and you might not be aware you need to treat a low blood sugar. Below 30, unconsciousness usually sets in, often followed by seizures. Below 20 for a prolonged period of time usually produces lasting cognitive impairment and can be fatal.

You also lose potassium—needed to avoid heart arrhythmias—from the sweat you didn’t know you were producing.

There’s a thing among T1Ds called “Dead in Bed Syndrome.” People go low, don’t have enough onboard glycogen to stop the Crazy Train, lose even more potassium, and dream of treating the low they know they’re having.

Without a glucagon emergency rescue kit administered by a loved one, they experience heart arrhythmias and often, die. It happens often enough that there’s a tradition among T1Ds of lighting a blue candle in memory of someone who has passed in their sleep from a severe low.

That gives a terrifying new meaning to “no wake zone”, one that all of us living with T1D take very seriously.

Going low in the water can be undetectable…and dangerous

As I mentioned above, when you’re swimming, you burn calories. How many in a unit of time depends on how hard you’re swimming, and that can vary. Your blood sugar drops, and you don’t know how much, so you don’t know what to do about it.

In open water, you can’t just whip out your glucose meter and do a finger-stick test, and your CGM transmitter can’t send a Bluetooth signal through the water. In races and events, touching the boat, even for medical reasons, is an automatic disqualification.

Some Type 1s come up with MacGyverish solutions for this problem. They put their CGM sensor on the back of their arm (note: it can still come off in the water after several hours, and securing it with Coban / Kerlix will chafe your underarms, ask me how I know). Or they put the sensor on their glutes, which should be mostly out of the water if they have decent form and aren’t treading water at the moment. Their crew / kayaker carries the swimmer’s cellphone with a CGM-paired “follow” app (such as Dexcom Follow) installed, to which the CGM can transmit a reading. If you’re wearing a compatible Garmin fitness watch, you can get your BG numbers on the watch if your phone is nearby to forward the numbers via Bluetooth. Or the swimmer wears a “passive” CGM such as the Freestyle Libre, which can be scanned with a “reader” (don’t drop it in the water, it doesn’t float!) while the swimmer is resting or treading.

If you don’t have one of those arrangements, it’s down to guessing how you feel. Your two best indicators of a low blood sugar, profusely sweating and shivering, are of no use to you in the water. You’re wet, so how can you tell you’re sweating? And you may be shivering because the water’s cold. Sometimes I can tell because my jaw begins to clench (probably a precursor to seizures) and my form goes all to hell.

As you know by now, I carry an emergency supply of maple syrup gels on my person, tucked under tight parts of my suit where they won’t float away. I like the maple syrup because it doesn’t upset my stomach and it’s actually high in potassium.

But it’s one more thing I have to worry about.

If it’s that hard, why bother?

Let’s get one thing out of the way quickly: I don’t have a death wish. Quite the opposite. I want to be able to do what normal people do without dying. That’s why I want to know what can happen and I want to know what I can do about it before it happens.

I don’t want to be limited by the well-intentioned but misplaced advice of people like my original endocrinologist from 1972 who told me not to exercise because it could cause sudden drops in blood sugar.

I want to be able to do not just the normal things, but the hard things too, safely.

Being scared into not doing anything because of what might happen is not only what took me down the path of avoiding exercise long ago, it’s also letting diabetes take your dreams away from you.

And that sucks. Steal them back if you have to, and never give up.

Knowledge is power

People shouldn’t have to find themselves in scary situations just in order to learn.

Dr. Sheri Colberg-Ochs wrote The Diabetic Athlete’s Handbook. It’s a fantastic starter’s guide for T1D athletes, but it ends where the road gets rough and the path becomes hard to find for people who want to push boundaries.

Then there’s the T1D community. Together we’ve made strides in helping each other figure things out, and that’s incredibly empowering! The Facebook group Type 1 Diabetic Athletes has over 13,000 members. A few years ago, I helped start a FB group of T1D Ironman and Half-Ironman finishers, Tough Mudders, cyclists, strongmen, and other “diabadasses,” called Diabetic Ultra Endurance Athletes, mostly so I could tap their experience. I even ran into 3 long-distance type 1 swimmers, including my good friends Karen Lewin and Erin Spineto.

They’ve all taught me important things. For instance: that recovery carbs are very important for replenishing spent glycogen and avoiding overnight severe lows; but that even more important is being aware that this situation can occur and doing what you can to prevent it. Fuel more. Dial back your basal insulin. You have to experiment to find out what works for you, but don’t get caught without a clue.

When I’ve found myself at the edge of knowledge, I’ve double-checked my logic, taken safety precautions, and taken the plunge into discovery myself. You have to sometimes.

Long distance swimming with Type 1 Diabetes is like driving with a snake that won’t leave your car. You can’t ignore it, you can’t fight it, and the alternative is not to drive. So you prepare for it, deal with it, and if you’re careful, learn from it and don’t get bitten.

And anyway, better the devil you know.