Your donations help T1Determined #keepgoing.

Event Report: Swim Around Key West (10K)

As you may know, after much consideration and fairly late in the game, I switched my 2022 participation in the College of the Florida Keys Swim Around Key West from the full 12.5 mile swim around the island to the 6.2 mile “half-distance” 10K swim. I wrote about that decision and the reasons for it here.

This is my report on the 10K (6.2 mile) swim.

A Late Start Led to High BGs

One of the great challenges to doing any endurance event with Type 1 diabetes is figuring out how to fuel for the event. For a swim, it’s even more challenging as most of your fuel must serve multiple needs: carbs, hydration, electrolytes, and providing some degree of muscle recovery. It also has to be consumed while treading water, since marathon swimming rules generally don’t allow for contact with the support vessel (usually a kayak or other boat) during the event. That means that as a practical matter, all my fuel has to fit into a “bike bottle” with a wide mouth that can be opened with one hand. The bottle is usually attached to the end of a rope with a carabiner and tossed overboard in front of the swimmer so that it’s impossible to miss a feed.

Pre-race, fueling is the normal stuff: whatever you’d eat right before a marathon or something similar. For me, that’s about 60g of carbs in the form of four Rice Krispy Treats washed down with bottled water. They’re easy to carry to the start, easy to dispose of, and hit my system fast.

Unfortunately, while the start of the 10K swim was announced to be 8:30 AM, that time actually turned out to be the time at which the athlete’s briefing for the 800 yard, 1 mile, and 2 mile swimmers was delivered, AFTER which there was an athlete’s briefing and a quick head count for the 4 10K swimmers out of the 6 that had registered. The actual swim started just before 9:30 AM.

By that time, my blood sugar was above 300 mg/dl (around 17 mmol). Since I felt reasonably good–not crampy or like I needed to pee–I decided to try to “burn it off” during the swim.

A Smelly, Nasty Kick-Off

At the start, the shore was sandy and the temps were already creeping up into the mid-80s (°F). Since I had just come from the Dallas-Ft. Worth area where temps were in the 100s, it didn’t feel all that bad, but I could tell from the sweat under my swimming cap that it was heating up a bit.

Down by the water’s edge a large mass of sargassum (seaweed/algae) hovered near the surface of the water and lay on the shore swarming with flies like a dead carcass. Race director Lori Bosco was kind enough to let the four of us 10K swimmers wade and paw our way through the sargassum before starting the clock.

Otherwise, Good Race Conditions

The water was warm. I estimated it to be around 84 degrees F, about 5-10 degrees cooler than what I was used to swimming in the Dallas area. Some people had warned me that the water would be exceedingly hot, but I didn’t find it to be unpleasant. I was more worried about the salt than the temperature, as my previous practice at Hobie Island Beach in Miami and at Sylvan Beach in LaPorte TX had both been fairly salty. The water in LaPorte is choppy when the tides go out and the winds are blowing in, good for practicing in rough water, and is brackish (half saltwater, half fresh water), so it’s not as salty as the ocean, whereas in Miami it’s all ocean and pretty salty. I had been expecting water as salty as Miami’s, but the water just off Key West didn’t strike me as all that salty, and it didn’t taste peppery like it did in Miami. Nevertheless, I tried to keep as much of it out of my mouth as possible.

The course was basically a single 4-mile loop followed by two 1-mile loops and a little bit more back to shore. The water was also very, very calm, even glass-like, shallow and extremely clear. The first 800 yards of the course were along a row of channel markers that made for easy sighting even without relying on my kayaker, Alan. As a result, I found it to be fairly pleasant going.

Our “Plan B” Fails after Half a Mile

Somewhere in the first 800 yards I swam into a large mat of sargassum, which feels a lot like swimming into a pile of cypress mulch. The seaweed tore at the “backup” Libre sensor I had mounted on my arm in case my Dexcom-Garmin setup couldn’t send or pick up a signal because of interference from the water. I made it perhaps another 200 yards before the Libre sensor and the waterproof overpatch that secured it came completely off at the next patch of seaweed.

After that, I strove to better avoid the sargassum, as it simply slowed me down, made it difficult to do much of anything, and even veering of course was better than swimming through it. But now my “backup” glucose monitoring system was gone and it threw me for a bit of a loop. For the next five and a half miles with my blood sugar already trending high, my Dexcom-Garmin setup, which I was operating in non-standard ways to avoid losing the Bluetooth signal, HAD to work.

At around 1200 yards my kayaker and I encountered a buoy that we later discovered was sort of a third-of-the-way marker, just past the end of the 8 channel markers that led away from the start. I swam on, and after the line of channel markers gave out some time later we encountered the large yellow (if I remember the color correctly) buoy we had been told was the far turnaround, near the Key West airport.

To Feed or Not to Feed?

At the buoy on the airport end of the course, my watch read 2100 yards and Alan’s read closer to two miles. That was the first inkling I got that my watch might be measuring distance more conservatively than others’ watches.

Alan announced that Dexcom Follow was reporting my blood sugar as just over 300 mg/dl, still quite a bit high. I didn’t feel at all dehydrated–after all, conditions were more favorable than they had been in Dallas a few weeks earlier–so when he asked if I wanted to feed, I told him I’d skip it and do a feed at the buoy on the other end, close to the starting point.

Before the swim, I had moved the Dexcom CGM (Continuous Glucose Monitoring) transmitter-sensor combo to my left glute. I knew that I usually sighted Alan on my left side when I took breathing strokes, and that my left hip would be closer to the top of the water most of the time and likelier to transmit a signal. Fearing I’d also lose the infusion port on my insulin pump if saltwater caused it to loosen, I had moved the site to my right glute, which was usually deeper underwater. That way, none of my critical equipment would come off in the water unless my shorts came off first (gratefully, they didn’t).

When we made it back to the first buoy near the starting line, I was relieved to see a Dexcom reading on my Garmin Fenix. My blood sugar was still in the high 200s but slowly coming down. I was also getting a pretty much constant blood sugar reading on my watch, so I relaxed a little.

Without those numbers, I’d be telling a very different story, and it wouldn’t be a happy one. To say I was grateful would be an understatement.

However, I had gone 4 miles and had at least 2 more to go, so I chose to do a feed even with my blood sugars still in the 200s. Now if you’re Type 1 and reading this, I know it sounds crazy and ill-advised to eat when your blood sugar’s high, but I had previously gotten into a similar situation running across both Iowa and Texas. My blood sugars had been running high from stress and dehydration and wouldn’t come down even when I bolused. And while it would have been possible to bolus while treading water, it would have been a bit like juggling while riding a unicycle and I chose not to do it.

During the runs across Iowa and Texas, I had taken some fuel, waited for my body to absorb it with just basal insulin onboard, and tried to destress as much as possible, and it had worked when simply dosing down the highs didn’t. That’s basically what I did during the swim. I’ve written a bit more about this strange phenomenon of stress, insulin, food and BGs here if you’d like to dig deeper.

Anyway, at the turnaround I drank around 8 ounces of my feed mix, Untapped maple syrup mixed with a whey shake. That got around 40g of carbs and a fair bit of potassium into my body, which I figured would get me through the remaining 2 miles while my body worked my sugar the rest of the way down to normal range.

After the feed, the remainder of the course was two loops of the roughly 1-mile course that the first and second wave of swimmers had encountered, plus the distance from the final buoy into the Finish. Since a lot of that distance was accompanied by channel markers that were easy to sight by looking “up” on a breathing stroke, I made reasonably fast time, for me anyway. When I looked down at my watch, I could see my blood sugars in the clear water and could tell they were trending down back into the normal range, so I relaxed a little more. I didn’t even mind the slight cross-current that slowed me down a little on the “return” parts of each lap. Oddly, it was probably that relaxing that helped keep my stroke efficient and allowed my blood sugar to normalize.

In the moment, I could only tell that things seemed to feel better. But as I looked at my watch, I saw conflicting signals. My pace was good, but my distance didn’t agree with Alan’s. That said, it had never agreed with my lake swimming buddy Scott’s numbers either, so I felt the error might be mine.

That said, I wasn’t sure enough about it to feel confident.

Doubts Creep In

Doubts about my pace crept in. I could recall one time when I stopped to look at my watch and the instantaneous pace jumped! Was it a bad satellite signal? Some kind of bounce, echo, ghosting, or other signal malfunction? What was my real pace?

When all else fails, I tend to assume the worst, so I did.

During training, my pace had been a subject of some debate. On nearly all of my 12-mile training swims, the open water pace reported by my watch was never faster than 2m:50s/100 yards. My Dallas kayaker Rick and I had attempted to reduce my feeding times as much as possible to speed up my overall pace. I had practiced both with and without him trying to sight as little as possible in order to help reduce unproductive time. After a fair bit of data collecting, we had determined that out of each hour of swimming, approximately 1 minute consisted of feeding, and sighting and current accounted for an unknown amount of slowdown. I thought perhaps that surface current at the lake might be an issue, so I experimented with swimming different routes that separated the current into head current and tail current, and setting the distance for automatic lap counting to be the distance to the buoy at the lake where the current reversed. The reported difference in pace could ALMOST account for the difference in pace between the pool and the lake, but not quite.

My wife and crew chief Leslie and I sat down with tidal charts and a spreadsheet showing my pace at each mile of the 12.5-mile swim around the island, figuring we’d catch a mild cross-current on the first 2 miles, a weak push from the back on the next 2-3 miles, dead calm from mile 5-8, and a strong tail current through Cow Key channel.

We had plenty of data from the lake, but as I always swam the same or similar course, it was possible that there was an element such as current that I had not managed to eliminate from my base pace estimates. We tried, but it was just impossible. We had to assume my best pace at the lake was my best pace in the ocean, and no matter how we calculated it, there was a minimum of 30 seconds per 100 yards that I could not account for, and every scenario we ran had me either barely making it to checkoffs before the tides reversed or not making it at all.

If the reality were any different, I didn’t have the right kind of data yet to prove it.

That was one of the reasons why we had decided I’d do the 10K instead. Another reason was that at half the distance around the island, on the SAME day as the actual full circumnavigation, I’d have a chance to get a “feel” for the water temperature, currents, saltiness, waves, and all the other things I had up until then just been estimating. Plus I’d basically have a number that I could double to estimate my finish time for the full 12.5-mile race.

Here in the actual event, I could see that my Garmin Fenix 6 was reporting my pace as a bit faster than I was used to seeing, but the distance measurements were discouraging. I didn’t know what to believe. In the clear, warm coastal waters that day, I had consistently been swimming a 2:06/100 pace, similar to my pool times. But my watch was also showing I had only done 5 miles, and that bothered me. My kayaker’s watch showed I had done 6. The course distance was verifiably 6 miles by a number of means–we printed out a Google Maps picture of the island with known landmarks and distances measured on land and transposed them to the marked course in the water. We checked with the other swimmers at the finish, and their watches reported the full 6.2 miles as well. We established without a doubt that we had turned at the correct buoys and that I had swum the same course as the other athletes.

During the swim, though, I had convinced myself that I was going much slower than the pace reported by my watch–the SAME pace I could consistently deliver in similarly calm conditions in the pool and occasionally at the lake, so it was believable–and as a result, based on my doubts about speed, I sped up. I just didn’t believe the numbers, because at least one of them wasn’t right (spoiler: it turned out to be distance).

The last two miles were similarly confusing. I knew how many laps I had done and what I still needed to do. I knew where I had turned and race officials in kayaks were observing and guiding swimmers so they didn’t cut the course short. But at that point, there were swimmers going both directions: to and from the western buoy near the starting line. I had been pacing with a lady just ahead of me who had managed to get a lead of around 400 yards on me that lengthened over time, so I knew I was slowing down as she sped up. For a while, I sighted on her kayaker partly just to give myself some motivation and partly because some jetskiers just off shore had kicked up some wake that made it more challenging to sight on Alan, who was on my left side toward the ocean. In time, they put some distance between us. I saw another swimmer coming toward me when I was on the first short loop (mile 5) and somehow convinced myself that he, too was ahead of me (he was actually behind me).

Good News Arrives

By my best mental math, I was second from last but doing okay, and when I was on finishing side of the last lap, Alan guardedly told me that I was “making good time.” I took it as encouragement, but I’ve been to enough “rodeos” to know that sometimes, folks say encouraging things to keep you from limping into the home stretch. That said, Alan had been ahead of me the whole way, just out of reach, and I know I had subconsciously accelerated to try to pull alongside him.

As I got out of the water, I noticed it was barely 1:30 PM. Based on my pace at the lake, I had figured a maximum speed of 1.2 mph, around 2:30/100 yds. Instead I had made 1.6 mph, or 2:06/100 yards. Even at the pool, I had never maintained that pace for longer than 2 miles before slowing down. Sure, I had made some pace improvements in the last few weeks leading up to the swim–principally, breathing every other stroke instead of every 3 strokes and lengthening my catch and trying to sight with my head lower–but I had no idea whether they had helped since I had so little reliable data from the lake swims owing to the fact that just about weekly I was trying something new and one week was not comparable to the next.

When I emerged from the water and waded and clawed my way through the sargassum, I casually asked how I had done.

“Second,” said a race official. That’s good, I thought: second in my age group. I would have been happier with first, given that there were only 4 swimmers in the event, but I’d take it. I asked her whether she meant second in my age group or second from last, since I knew there was another swimmer behind me.

“No, second,” she said, emphasizing the word this time. “Overall.”

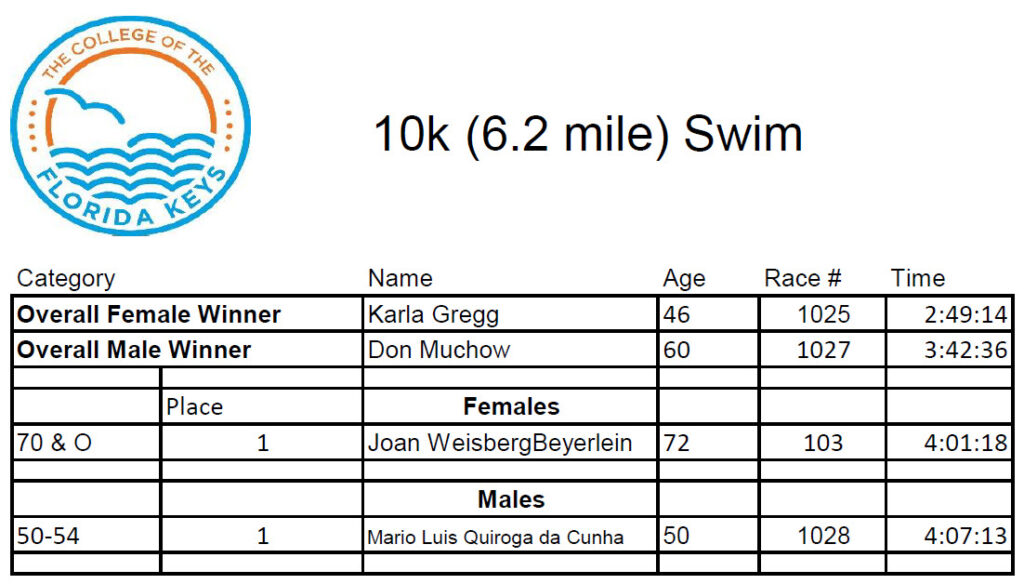

For th10K results click here or view the image below.

My finish time was 3h 42m 36s. That’s not elite, but it was fast for me, and it was faster than most of the other 10K swimmers that day. Maybe it’s better for me to think I’m always in the back, and that they’re just short of rolling up the ocean behind me and flipping a sign on the beach from “open” to “closed.” I don’t know.

I have no idea how I came in second overall and first place male. All I know is that the weather was perfect, the water was perfect, I was feeling good that day despite high blood sugars, and maybe just maybe since I skipped some feeds I gained a few minutes on some of the other swimmers. I know that trick’s not going to work on a 12.5 mile swim, but I’m grateful that it served me well for the event in which I participated. I’m also thrilled that somehow, somewhere, I managed to make improvements that mattered. I’m even grateful that my watch “lied” to me, which motivated me to be faster.

In the coming weeks, I’m going to test the distance reported by my watch vs my Garmin InReach satellite beacon and a couple of older watches just to see if there are any mental or other adjustments to make. I’ll continue to work on technique and cross-train. I’m even planning on doing a quintuple iron-distance triathlon to celebrate the 5 decades I’ve lived with Type 1 diabetes and to keep myself in good condition for 12.5 mile swims (roughly 5x the 2.4 mile distance for a typical Ironman event).

I still think about how cautious I was going into this, and I don’t for a moment regret it. It’s data, I needed to know, and it’s actually encouraging to have a marathon swim officially under my belt and a pace that encourages me to think I could do the full swim around the island next year.

We will see what is in store for the coming year of training. With luck, I’ll be back, stronger, better, and maybe even a little faster.