Your donations help T1Determined #keepgoing.

Kurukshetra Within: Battle and Balance in the Struggle with T1D

Diabetes Insanity

“Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.“

— Rita Mae Brown (often misattributed to Albert Einstein)

“Diabetes insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting the SAME result.”

— Me

I am, overall, a reasonably well-controlled diabetic. I count carbs (about 150g a day if you’re curious). I eat balanced meals and get regular exercise. I don’t try to “get revenge” on diabetes by stuffing my face at Cheesecake Factory.

Even so, recently, I experienced over two days of unexplainable high blood sugars.

The REASONS blood sugars might be out of range are numerous: not just inactivity, overeating or underdosing, but also OVERdoing exercise, as well as illness, stress, hormones, kinked or wrinkled insulin pump infuser cannulas, scar tissue or infections at the infusion site, pump tubing occlusions, suspended delivery due to pump malfunctions, incomplete boluses, or unfinished cartridge loads, plus dehydration, drug side effects (particularly steroids), sleep deprivation, rheumatic or inflammatory conditions, or expired insulin, just to name the less weird and exotic reasons.

In case you’re counting, that’s around 20 reasons. And that doesn’t guarantee the ACTUAL reason for the unexplained high is at the top of the pile when you go looking for it.

Yesterday, I discovered that the vial of insulin I’d successfully drawn from to fill cartridges for most of my holiday travel time had decided it was expired. Not expired in the sense of “best if sold by”, like when you get cheap, slightly brown ground beef at Kroger for half off. My so called “life water” (a term used by some diabetics to refer to insulin) had no more life.

That type of expired.

Forget the fact that nearly all of the vial had worked perfectly up until that point. THIS time the result was different, lasted two days, and took Sherlock Holmesian sleuthing skills to figure out.

“I don’t WANT this fight.”

There’s a scene in the Bhagavad Gita where Prince Arjuna, leader of the Pandavas, stands against his cousins, the Kauravas, on the battlefield at Kurukshetra. Arjuna tells his right-hand-man, Lord Krishna, that he doesn’t want to fight. Krishna tells Arjuna that this battle is both his destiny and duty as a warrior. Arjuna is frustrated. After Krishna tells him the battle will be fought a thousand times with no change in the result, he feels like there is no way out, at the same time Krishna counsels him to not give up the fight.

I felt like Arjuna. I didn’t WANT to fight my equipment. I didn’t want to lash out at some vague, ethereal concept called “diabetes” either. It wasn’t actually fighting me, and it didn’t care whether I fought or not. And my medical team wasn’t at fault either. I hadn’t seen any of them for weeks. But I couldn’t just SIT there and do nothing. I would have given ANYTHING for some insight into the situation.

Instead, it took me almost two days of eliminating all the OTHER causes of the highs before I realized that nothing was wrong with my equipment, that the problem wasn’t anyone else’s fault, and that it wasn’t mine either. My activity levels were fine. My diet was fine.

BUT my ketone levels were up, and that was a clue I hadn’t thought to check. It meant I wasn’t getting insulin, or the insulin wasn’t working.

At least now I was moving forward.

The most memorable, most valuable lessons are ALWAYS like that.

The Importance of Data Analysis and Non-Judgment

During my recent investigation into why I was experiencing persistent high blood glucose readings, I went through several hypotheses:

- Highs were due to diet: basically too many carbs. This proved to NOT be the case, as during the data-gathering phase, I basically ate a homemade pork broth soup similar to pho, minus the noodles.

- Highs were due to a failure to adjust dosage for fat and protein: also not true, since I was consistently adjusting.

- Highs were due to stress: During those two days, I was not feeling any unusual physical OR psychological stress, though I always get nervous about having to blend holiday family visits with working long hours leading up to Black Friday (spoiler: I’m not very good at it). And while my blood sugars ran “high and flat”, which is typical of stress, stress doesn’t usually produce ketones for me unless I am burning significantly more calories than I’m eating–for instance, during a transcontinental run.

- Highs were due to medications: I wasn’t taking any steroids and hadn’t changed any other meds.

- Highs were due to a badly inserted infuser: Usually I can “feel” when I’ve hit scar tissue, a blood vessel, or made some other error inserting an infuser, such as going in at too sharp or to shallow an angle. After two re-dos, I ruled that reason out as well.

- Highs were due to an unreported occlusion in tubing: Although this was the suspected problem in 2015 when an occlusion in my tubing appeared to suddenly clear, delivering an overdose of insulin and sending me to the ER, this wasn’t the case. I was getting insulin and it was “sort of” working, but it just wasn’t working very well.

- Highs were misreported due to calibration error: hypothesis proven incorrect after multiple manual finger-stick glucose tests confirmed my CGM readings were correct.

- Highs were due to dehydration, sleep deprivation or some other physical condition: While plausible, my blood sugar was consistent regardless of how much sleep I had gotten.

- Highs were due to excessive exercise: Unlikely, since I have long since recovered from my 10x Iron triathlon challenge and am back to regular short runs on the treadmill along with daily walks of a mile or so.

All were based on the idea that I had not exercised, exercised too much, eaten the wrong thing, dosed incorrectly, or installed or used equipment incorrectly. The only other possibilities I had considered all clustered around the problem being somebody else’s fault.

Data is blameless, non-judgmental, and enlightening.

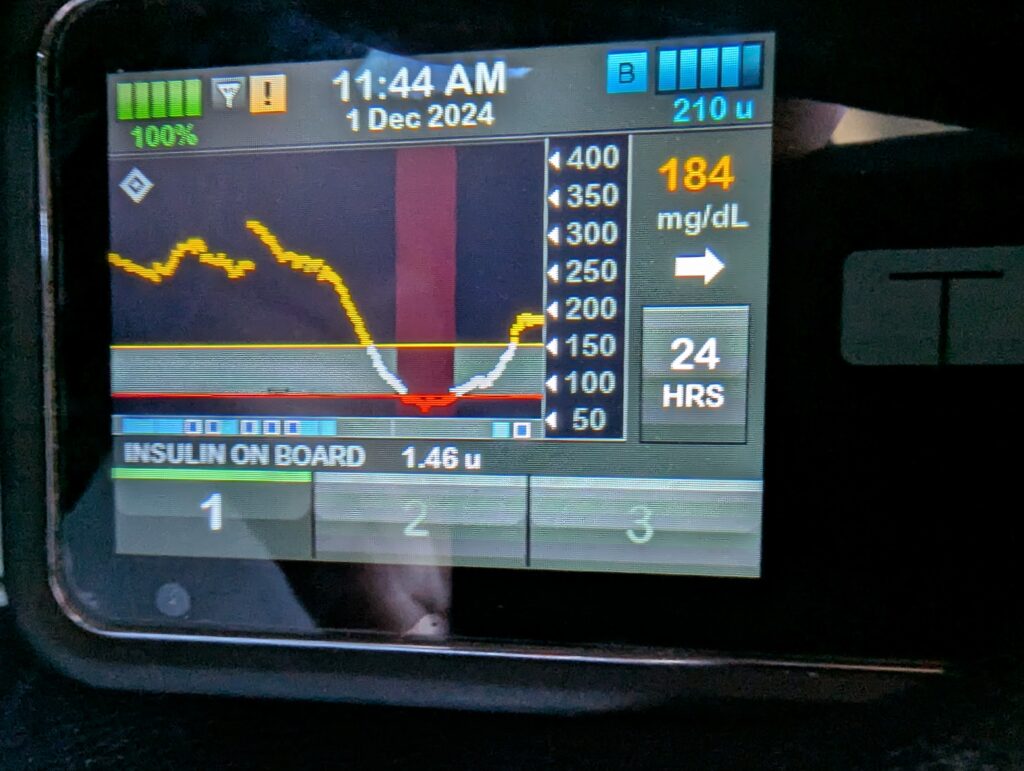

Somewhere in it was the answer. So for two days, I watched my Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) trends intently. From what I knew:

- Too many carbs looked like a sharpish upward climb that responds well to insulin and goes back down. I wasn’t seeing that.

- Glycogen dumping is a similarly sharp spike that responds well to recovery carbs and protein. I wasn’t seeing that either.

- Stress looks like a slow climb up into the 250-300 mg/dl range, with a long flat plateau following. It doesn’t respond well to dosing, but does respond to food. No matter what I ate–or didn’t eat, nothing changed.

- Occluded tubing looks like a long, slow rise in blood glucose levels and less insulin is delivered with each dose…until the occlusion breaks and sugars drop precipitously. So far, I hadn’t seen that, and at one point, I was sitting on top of 8 units of insulin, a level I hadn’t had on board since 2004. But the stacked doses were making me anxious.

- The CGM graph for occluded tubing and infusers, illness, and “cooked” insulin all look similar. That gradually became my operating theory, but since I didn’t feel ill, the only way to tell is to replace the parts until the only thing left is either “bad insulin” or a sudden, unexplained change in insulin sensitivity.

After ruling out causes that didn’t match my CGM data, I checked and discarded multiple types of supplies before concluding they weren’t the problem either.

It was cooked insulin for sure.

As soon as I changed out the old cartridge for a new one and filled it from a fresh, unopened vial, things went back to normal within a couple of hours.

Lesson Learned

With diabetes (regardless of type), it’s important to understand exactly what battles we’re fighting and to not attack the wrong opponent.

For a while, I considered leaving the insulin in the cartridge because I was convinced it was not the problem. Of course, that is Diabetes Insanity. It WAS cooked insulin. Even though several hours earlier it was fine.

When a problem pops up, you have to check the data. All of it. Until you find an answer. Until you can explain what you’re seeing. Until once again you can move forward.

You cannot waste time attacking your allies or blaming your equipment unless one of them is PROVABLY at fault, no matter how how much it feels like you should. That’s the easy way out…and it’s also the WRONG way out.

I’ve got an endocrinologist appointment coming up in the next month, and it would be very tempting to just sit there frustrated while he or she looks at my data and tells me what I didn’t do, what I don’t know, and how I don’t have a handle on things. And that’s not just a pitched battle against my own allies, but one that’s been fought a thousand times before with the same pointless result.

It would be easy to blame the equipment, the insulin maker, or diabetes itself. After all, after 50 years, I have a right to be frustrated. I could lash out against them all, or refuse to fight them and give up. But in doing so, I would give away the very agency I need to find answers.

Instead, the two of us will consult together, look at the data, and talk about what went on this last week. We won’t make any knee-jerk basal adjustments or change carb ratios dramatically–unless the DATA show a trend persisting well beyond the last few days. And that’s fair…we can talk about that.

We HAVE to talk about that.

Because, dear endocrinologist, my fight is not with you, nor is is with diabetes, nor the equipment, nor even myself. It is, rather, with the notion that the data itself is something or someone separate and allied against me. That is a tempting idea, but it is a falsehood.

And that truth, like Arjuna’s realization on the battlefield, is forever dawning on me.