Your donations help T1Determined #keepgoing.

The 411: Exactly How I Ate, Drank, Tested, Treated & Ran Across the US With Type 1 Diabetes

NOTE: This post was written by Leslie, my dedicated wife and crew chief, who not only “encheferized” all 2845 miles of the US run, 851 miles running across Texas, and 349 miles across Iowa, but kept track of calories, carbs, fat, and protein to ensure I started each day as fully recovered as I possibly could and didn’t lose weight from metabolizing too much of my own body. In other words, If I was the astronaut, she was every single person in Mission Control who keeps the rocket flying.

Spoiler: it’s a little more complicated (and interesting!) than Eat. All. The. Foods.

Gels, moderate drops in my basal rate, and to be honest some pretty crazy blood sugars got me through 5Ks, half-marathons, marathons and even a couple of 50Ks.

But what got Don through Kansas, Iowa, Texas and the United States was completely different.

Four years and 4000 miles since Don started doing super-long distance, here’s how he’s learned to fuel, hydrate and deal with high and low blood sugars.

NOTE: For non-US readers, to convert blood sugar mg/dl into mmol, just divide the number by 18. But you already know that. 😉

Simple, but not easy.

Here’s the one thing Don and I know for sure: Athletes with Type 1 diabetes who do extreme ultra endurance events need ways to get calories that make sense, regardless of whether their blood sugar is high, normal, or low. Success absolutely depends on making it easy to pivot from one food and/or liquid to another depending on the need of the moment.

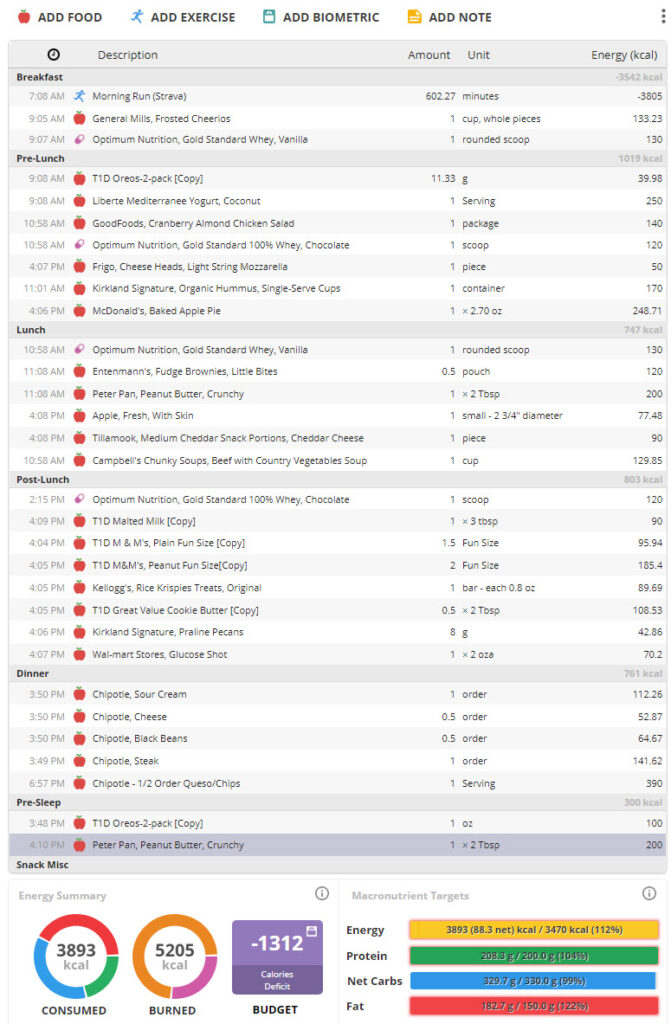

If you’re like Don, you’re looking at the chart, so let’s get some obvious stuff out of the way. This was a typical day, and I usually ate around 4000 calories but almost always burned 5000+. Losing weight was no joke, and he had to adjust his eating to get more fat and protein on board–fat for the calories and protein for muscle recovery.

But let’s get to the carbs first.

Lesson 1: Keep your carb options open

We firmly believe in carbs for prolonged activity, even though Don eats pretty low-carb at home (50-100 grams most days, not counting fuel during workouts). Research backs up the idea that eating carbs during exercise improves and sustains athletic performance and helps replenish glycogen, but we arrived at this approach just based on real-life experience.

Figuring this out started back in 2017, at the crewed Honey Badger 100-miler in Kansas, in July (!). Then, we were fairly clueless about the effects of stress on blood sugar. Don had super-painful full-foot blisters by about Mile 50 despite our best novice blister-prevention efforts, and a terrifying midnight encounter with a homicidal truck driver, plus asphalt temps well over 120F, all added up to frighteningly high blood sugars.

We actually wondered five miles from the finish whether he would a) not finish, b) come in DFL (dead f&^%ing last), or maybe, just maybe, do better than that. He finished in 34 hours, 2 hours before the final cutoff, finishing ahead of just one other runner, a fellow who had promised himself just one last 100-mile run before an invasive operation to treat lung cancer.

Suffice it to say, it was a beatdown, and a real learning experience for us both.

To top it all off, we were relying on fruit whole-milk yogurt as the primary fuel source. It worked pretty well during 40-50 mile training runs, so we figured it would work at Honey Badger. (LOL. Every Type 1 knows the definition of insanity is to do the same thing twice and expect the same result. What were we thinking?!)

Sure, yogurt had plenty of calories, protein and fat—but the sugar made it a terrible option when all these stress hormones spiked his blood sugars. We had no slow carbs with us, virtually nothing low-carb, and with one and only one convenience store on that entire 100-mile route (at mile 50), there wasn’t much we could do about it.

So mostly, since his sugar was running high from stress, he just didn’t eat after the 50-mile mark, something like 16 hours of non-stop exercise with one solitary cup of yogurt, as I recall.

But of course, all that pain and stress and heat, plus not eating, just made things worse. The level of physiological stress was through the roof. And even when your sugar’s high, during prolonged endurance exercise you still crave FOOD. Without it, your body stays in “survival” mode and continues to dump glycogen.

Some of you are probably thinking, “dose a little.” But the idea of dosing or “exercising down” a high BG only works when you’re not already pushing your physical limits. Even if you add more insulin, all it will do is temporarily re-store the glycogen, which your liver will dump again because of stress. This showed up on Don’s continuous glucose monitor’s blood sugar graph as a set of “scallops”: repeated dips and subsequent rises in blood sugar despite the lack of food. You have to remove the stress (by activating your parasympathetic nervous system, the one that tells you “the cheetah is gone and it’s safe now”). Sometimes slow, deep breathing, meditation, or yoga can help with that. But mostly, eating helps.

That’s right. Even when your blood sugar’s 300 mg/dl.

The main thing we learned was that when that was the case, we needed energy sources that didn’t exacerbate high blood sugars while at the same time reducing stress by tricking the body into thinking everything was A-O-K despite the blisters, lack of sleep, and high BGs. It was obvious before the Kansas run was even halfway over that going forward we needed to plan on bringing more than just sugary stuff, so Don could get calories no matter what his BGs were doing.

One lesson down, many more to go.

Lesson 2: Type 1 risk management isn’t just about food

Honey Badger was training & experimentation for 2017’s solo 223-mile Capital to Coast Relay from Austin, TX to Corpus Christi, a race that averaged about 65 miles/day over roughly 3½ days. Fuel and sugar-wise, C2C was pretty uneventful despite the high daily miles. We knew this route well, had cool temps and great running company (Josh was an absolute professional pacing me), no homicidal drivers, and much better blister prevention and treatment. The biggest source of stress was just lack of sleep (7 hours in 4 days), so the fueling and blood sugar situation stayed pretty stable until the very end of the run when blood sugars drifted down and stayed around 60-70 mg/dl. Still manageable, though.

But let’s back up here. Sleep was a BIG issue. In fact, THE biggest one.

Extreme fatigue is standard in the ultrarunning world, but most of those runs are on trails, not roads, and those runners don’t have Type 1 diabetes. It was pretty scary to see Don running right next to traffic when he couldn’t form a complete sentence, couldn’t remember his own birthday, and could hardly stay awake. That did not bode well for hypoglycemia awareness. It felt super-scary to both of us. His own ability to decisively and quickly treat a low was in question. Josh Fabian, the Type 1 ultrarunner who paced him, was alert and attentive to Don’s situation (like I said, an absolute professional), but we knew sleep management would be an issue for future runs.

Lesson 3: The best-laid plans…

In June 2018, Don became the first person to run Relay Iowa (339 miles) solo from Sioux City to Dubuque, the entire width of the state, averaging 40-45 miles/day over roughly 7.5 days. This time, we packed more low-carb foods and by now were much smarter on blister treatment and prevention, which helped to reduce stress. The biggest change was that we specifically targeted 7 hours of daily sleep, vs almost none at Capital to Coast. After C2C, Don learned the value of cutting his planned daily miles to make sure he could keep up the pace for a week.

Then reality intervened. The daily miles were indeed lower at the beginning, but multiple extra-long days trying to make up miles lost to a series of thunderstorms and tornados really took a toll (there were 4 thunderstorms, one spawning a tornado east of Dyersville, where the Field of Dreams is located. There’s a reason the movie Twister was filmed in Iowa–even without the special effects, the state is Tornado Central, and the weather can get super dicey.

The good news was that despite the weather delays and long run days, we stuck to the planned sleep schedule until the final 24 hours—but the bad news was that this created lots of self-imposed pressure in order to finish by our original deadline. To put this in perspective, the race director cut the route short about 20 miles for the relay teams due to weather. We, on the other hand, were determined to cover every single mile, AND to do it as close to the original cutoff as possible.

So when Don’s BGs started running predictably high, we knew fueling with carbs without insulin didn’t make sense. But getting more insulin tended to light a fuse that exploded an hour or so later in persistent lows during the late afternoon and evening while he was still running, bottoming out right before we went to bed. We adjusted basals, boluses, correction factors, carb ratios, the whole nine yards, but never really felt like we had a handle on it.

It was so, so frustrating and depressing for him to have to sit on the roadside and wait. And wait. And wait some more, until the food he just ate finally kicked in so he could kinda sorta run again. I remember one day in particular when it took us an hour to cover the final two miles to the hotel because that’s how long it took his sugar to come back up. What I’ve seen from his experience is that it really messes with your mind, especially when the sun is almost out of sight and your day is nowhere near done.

By the last day of the run, this cycle cascaded into a intense physical beatdown and easily the darkest mindset Don had drifted into during any of these runs. Just putting one foot in front of the other after nightfall on the last day was all he could manage. At one point about 13 miles from the finish, I told him to sit down and rest, and he said, “No. If I sit down, I won’t get back up.” If you know Don, you know that’s out of character.

He made it to the finish line at the Mississippi River thanks only to Christa Palm, a fellow Type 1 diabetic runner who met us at Dubuque’s city limits and stayed with him all the way to the end, encouraging him constantly that the finish line was “just past the next street.”

It was hard, hard, hard. We were trying to avoid the mistakes we had made in Kansas; and without question, the changes had helped some. But after Iowa, we both said “OK, that actually sucked. We have got to figure some of this stuff out better before we do something like this again.”

Lesson 4: A new take on insulin & food

After Iowa, we settled on three key principles:

Principle #1: Insulin is for blood glucose. Food is for energy.

Put another way, eat the calories you need to fuel your activity. Then use insulin to make your blood sugar behave.

Many Type 1 folks learn to do just the opposite on a day-to-day basis: if you’re high, you skip eating as much as you can stand, and wait for the correction bolus to kick in, right? If you’re active, you probably exercise to help bring it down even faster. It’s not fun, and no one knows “hangry” like someone with Type 1 and a high blood sugar who hasn’t eaten more than a few nuts in 16 hours because they’re determined to work it down and resist the temptation to rage-bolus.

Don does that himself at home. But that approach is a complete dud in the middle of heavy endurance exercise.

The constant calorie burn leaves your body screaming for fuel. When you don’t provide it, your body starts breaking itself down for fuel. That leads to a spectacular failure spiral in a multiweek/multi-month scenario: crappy energy levels, dark mindset, muscle breakdown, greater injury risk, less recovery during and after.

Basically, Iowa.

Lesson learned: Fuel for the activity. Then adjust insulin as needed for highs and lows.

Principle #2: Always fuel on schedule.

Adapt what you eat to your blood sugar, but don’t skip fueling. As Don would say, “Eat. All. The. Foods!”

High blood sugars can persist for many hours under stress, so especially in these conditions, you can easily end up missing thousands of calories if you skip food entirely until your sugar’s normal-ish.

Getting 4000 or so calories during an extreme ultra run is already hard. Doing it without eating is impossible (keep in mind that fat is around 3500 calories a pound). If you skip even a couple of fuel breaks, you’re missing 20% of your calories for the day, and you probably won’t make them up anywhere. You also have to ask yourself how you’re going to replenish glycogen if you’re not eating enough, which then raises the question of how well glucagon will work should you need it.

Prolonged exercise with no food grinds you down physically and mentally as your body uses itself for fuel. You not only lose body fat and muscle mass; you also recover less overnight, leave yourself more prone to injury, and your outlook goes to hell.

On something like a transcon, one of the most dangerous consequences of pressing on when you really ought to stop and eat is losing appetite entirely. In extreme stress, your body can start to shut down. It’s called “failure to thrive“, and while it’s mostly an issue with infants and elderly people, it’s a serious consequence of anorexia, a documented comorbidity of PTSD and can affect anyone in a prolonged state of stress. Once your body decides it doesn’t need food anymore, it’s hard to turn back, and the therapy to reintroduce feelings of hunger is not simple.

It’s hard to get enough calories onboard during a super-ultra distance run. It’s even harder to start the next morning fully fueled if your body’s given up and your mind just doesn’t know it yet.

Principle #3: If BGs are high, replace most carbs with fat and protein & dose (a little)

It’s great to say “fuel on schedule” but the immediate question is “Fine, but what am I supposed to eat if my blood sugar’s 240 mg/dl?”

You’re clearly not going to want to dose aggressively, because BGs often drop really, really fast out here, especially once you stop and rest. So the question of “what to eat” is a big deal. It’s not a theoretical question!

Fortunately, macronutrients only come in three varieties: carbs, protein and fat. That’s it.

If you’re not eating carbs (or can’t eat carbs right now), you’re eating fat and protein. Simple as that.

I’ll say more about this below. For now, the key point is: Make Sure You Get The Calories, because if you’re not eating something, your body burns itself for fuel (including muscle protein!).

A side note: I’ve run across quite a few “run fasted” fans, so let me tell you why I think that’s a bad idea, at least for folks with chronic inflammatory conditions. One of the consequences of metabolizing your own energy stores is that after going a while burning fat, you burn protein: specifically, your own muscle tissue. Broken down myoglobin stresses the kidneys and can lead to rhabdomyolysis as well as increasing capillary permeability, which can aggravate already existing inflammatory conditions. While increased capillary permeability might be helpful in clearing damaged muscle tissue, also allows so-called “microbial translocation“, which is a fancy way of saying that gut bacteria can enter the bloodstream as the blood vessels there become more permeable.

Speaking from experience at the 2016 Texas Quad, that was some serious intestinal distress along with a really bad case of hives.

I know that lots of people run hoping to lose weight, but at these distances, few runners need or want to lose weight, and certainly not muscle.

Lesson 5: It’s called “practice” for a reason

So, those principles sound pretty good, huh? Eat real food. On schedule. Whether your sugar’s high or not.

We thought so too, and we were determined to live by them when Don started his run across Texas.

Initially, it worked pretty well.

Then Don had a hard low in Odessa—BG of 30 mg/dl with double-down arrows, 2 units on board, faded out on me after nearly 100 grams of fast carbs didn’t help at all, and we had to resort to glucagon. Pretty damn scary.

Long story short, it was an extra-hard run day after we belatedly realized that TX-302 was one of the most dangerous roads in the state (thanks, Random Stranger, for stopping to tell us). We converted meals into snacks to save time and as a result undershot total calories. Then, when we stopped for the day, Don was already low, dosed for carbs, wasn’t that hungry, so actually ate almost none. The perfect storm, right?

After Odessa, we were so freaked out we sort of lost the signal on our original plan for a couple of weeks.

We were both scared about dosing for food or highs. We relied mostly on low-carb food to avoid having to dose. I still remember sitting in the Big Spring, TX Whataburger as we spent 15 minutes with Don’s BG at 300 mg/dl trying to come up with the right dose for a kid-sized burger that would strike the perfect balance between killing him fast with a blood sugar of 25 mg/dl and killing him long and slow with a blood sugar of 400. And knowing that no one anywhere really knew the answer.

Because as everyone with Type 1 diabetes knows, the insulin that keeps you alive today is the insulin that puts you in the ambulance tomorrow. Or lands you in the middle of what doctors love to describe dispassionately as “complications” years from now. No pressure, right?

When Don did dose, it was about as effective as water. No matter what we did, it seemed like his sugar never came down. We were starting to question everything we thought we knew. Could it be the protein shakes? Was it stress? He swapped infusers, tubing, cartridges. Used a syringe to rule out possible pump problems. On and on and on, desperately trying random things with no effect. And all the while running all day, every day.

Eventually, he swapped out the insulin in his pump cartridge with some from a brand-new bottle and dosed.

His sugar finally came down, just like it was supposed to. Turns out “gravity still works” after all, and when all else fails, it may be time to toss out the insulin itself and try a new batch–but you can really start doubting yourself in the middle of situations like this and sometimes it’s the last thing you try that works.

Meanwhile, I lugged a sack full of regular soda and juice and Smarties plus a handful of glucagon kits into every hotel room we stayed in during the rest of the run, hauled it up to the rooftop tent every night we stayed at an RV park. Set multiple alarms every night because we just weren’t sure he wouldn’t go dangerously low while we slept.

I knew that 8-pound sack of soda wasn’t totally rational, but ask anyone with a Type 1 spouse or partner. If you know, you know.

Texas: Lessons Learned

Texas was nearly 2.5 times longer than Iowa, and it was at least 2.5 times better, too.

Don ultimately made it to Texarkana on schedule, in good shape with minimal blisters and a consistently positive outlook that carried him all the way to the finish (Hi, Walt & Lila!). His only injuries were short-term tendonitis and a pinched nerve in his back which quickly healed after the run, both due to road camber. We both think the biggest difference was the focus on calories and protein combined with a willingness to slip the schedule when we hit a weather delay vs trying to make up the distance.

Odessa was awful, but it’s served us well since then as a never-forgotten and painful reminder: no matter what else is going on, you can never, ever take your eye off Type 1 diabetes. Every distraction is an opportunity for T1 to pounce:

- You’re busy swapping shoes or taping a would-be blister…and you forget that this stop was supposed to be a fuel break, too. 30 minutes later the van pulls up because the Follow app is screeching that you’re 75 with double-down arrows.

- You finish your 45-gram fuel break just as another Type 1 spots you and pulls over to say hi. Before you know it, your BG’s 270 and the last thing you want to do is run.

- You’re freaked out by an aggressive dog who charges towards you, and lose track that you were getting ready to test because you thought you might be low and before you know it yeah, you are low

- You meet, greet and walk around Disney for a couple hours, ride “it’s a small world,” don’t notice your sugar has drifted down to 85 and your insulin delivery’s suspended, and start running again without refueling.

Don hasn’t had those exact experiences, but he’s had very similar ones. Those examples illustrate our biggest takeaway from the Texas run: the most important time to remember your protocols is precisely when distractions come up.

How We Think About Nutrition

How many calories are enough? Well…

We both thought after Odessa that under-fueling was an issue. As we planned for the U.S. run, we tried to nail down the calorie count and target macronutrient levels more specifically.

Don’s tested BMR is 1600 calories/day, which is roughly typical for many people, so his daily goal is around 4000 calories, or 2.5X his BMR.

Research suggests that even during prolonged endurance activities, the average human can metabolize only about 2.5 times his or her basal metabolic rate (the calories you need just because you’re alive).

That means that even with highly disciplined fueling, you can only cover part of your effort through food consumption. Any additional energy required to fuel the effort has to come from breaking down body fat or muscle.

Alex Hutchinson has a good overview here of the underlying study: https://www.outsideonline.com/2397917/human-endurance-limit-study

One thing we’ve learned is that tracking calories is really helpful. I kept casual notes on calories during the Texas run, and that wasn’t good enough because Don lost about 7 pounds. For the U.S. run, I switched to an app to track intake, which turned out to be incredibly useful. More on that below.

Macronutrients & potassium

We have specific goals for protein. The carb and fat numbers fluctuate from day to day depending on what’s needed to meet the calorie goal while keeping blood sugar in range.

Carbs are great for quick energy and faster running. We think of fat and protein as “time release” macros. Fat’s a great slow-burn all-day energy source that’s ideal for very long-distance runs and transconning. Protein protects lean muscle mass and speeds recovery.

Macronutrients became a special focus after Iowa, where we didn’t emphasize protein or track calories closely at all. Underfueling really seemed to undermine physical resilience, energy and mindset during the final days of the race and dragged out recovery.

Starting with the Texas run, we aimed for about 175 g of protein/day. This is based on McMaster University research that found that athletes maximized retention of lean muscle when they consumed 2.4 grams of protein for every kilogram of bodyweight.

For Don’s runs, that protein comes from a mix of protein- and calorie-dense foods like egg salad, chicken salad, peanut butter, cheese, keto cereal, and whey protein shakes.

We also track potassium.

After a severe low a few years back, we learned from the ER doc that hypoglycemia lowers potassium (a lot is lost when you “sweat out”), that many T1’s are actually deficient in potassium, and low systemic levels of potassium can cause heart arrhythmias.

(By the way, leg cramps result from nerve signaling electrical glitches, not potassium depletion, so we keep HotShot handy for those, although for Don they’re pretty rare. It works great.)

Eating patterns & food variety

You really have to figure out your own eating patterns for super-long endurance events. That includes knowing what works for any health issues you have that affect your food choices.

It’s not just folks with Type 1 that have to think about this.

Our friend Elaine, an endurance cyclist we met in Sonoita, AZ, is gluten-intolerant. She’s learned the hard way that even on organized, paid multi-day group rides that promise gluten-free options, she has to pack her own food to make sure she doesn’t go hungry. Sound familiar?

Consider questions like these:

- Are there certain types of food you must have or can never have?

- What kind of foods can you tolerate when you’re exhausted and overheated? (for Don, it’s anything “wet”–he can’t stand even his favorite peanut butter when he’s dehydrated!)

- What kind of foods keep you going if you’re exhausted and freezing? (Soup or hot chocolate!)

- Is there anything you’d look forward to eating under those conditions?

- How much food can you eat at once without any kind of digestive issue?

Whatever those answers are, they probably look nothing like the way you eat at home, and they may not look like the way some other runner eats, either. Don often says that during super-long ultra runs, his stomach reverts to that of a seven-year-old boy: he wants nothing but Campbell’s soup, Oreos, cheeseburgers and chocolate milk.

Focus on what works for you. Some ultrarunners can slam down thousands of calories in a single sitting; yet that much food at once would make other runners sick. Human beings can generally only metabolize about 60-90g of carbs/hour, even during prolonged activity, so anything in excess, while it might be delicious, is just going to make your sugar higher if you’re diabetic.

If you have Type 1, we both think it’s critically important to practice eating and tweaking basal and/or bolus as needed during your ultra distance training run, under controlled conditions. Whatever worked at marathon or even 100-200 mile distances probably won’t work the same way at multi-week or multi-month distances.

Then, as the saying goes: lather, rinse, repeat.

What worked best for Don was getting around 300-400 calories from actual real food and/or liquids about every 45-60 minutes. That’s around 10 fuel breaks/day. For him, going longer between fuel breaks has tended to cause more lows.

Sometimes to save a little time, he’ll take individually wrapped components like cookies or applesauce or string cheese with him and eat on the move.

Hydration

We did some research into water requirements after the Honey Badger 100 race, which required (and checked!) that each team had 12 gallons of water and 30 pounds of ice for an event that lasted at most 36 hours.

Turns out that humans with normal kidney function can utilize no more than about 27-33 ounces/hour of water, max, before hyponatremia starts to become an issue. So in general, there’s no point in trying to slam down more than a couple standard-sized 16.9 bottles of water an hour, or one 33-ounce 1-liter bottle. There’s some research that suggests that 30 ounces at a time may not be optimal but we haven’t worried much about that.

Don just goes by how he feels: plain water when he feels like a wilting plant, and Gatorade or similar when it tastes sweet. His experience has been that if Gatorade tastes salty, he probably isn’t low on electrolytes.

We’ve done so many hot-weather events by now, though, that drinking on every fuel break is just part of the routine. I don’t push him to drink more unless he looks like he’s out of it, which he seldom was during his transcon.

Our planning assumption is conservative, so we assume 32 oz/hour of liquid for each hour of running. That means we carry more liquids than we actually end up using, but sometimes it’s hard to find water in remote areas. This gives us enough margin to comfortably get from one resupply point to the next one, plus van housekeeping and anything else we need water for.

That translates to six 5-gallon military water cans plus diet root beer and a handful of 6-ounce mini cans of real soda, because if his sugar’s low enough to justify real root beer and Dr. Pepper, you better believe we’re gonna be ready!

During the day’s running, we work from two five-gallon jugs and replenish those from the water cans as needed. One’s plain water, the other is a 50% mixture of Gatorade Endurance powder, something he came across during his 2017 finish of Ironman Texas at The Woodlands. We use Gatorade Endurance because it’s got potassium and three different carb sources (dextrose, maltodextrin and fructose) which has been shown by research to improve fluid absorption and carb metabolism. Sometimes for flavor I’d throw in a packet of Crystal Light to make it taste better.

That gives him a “basal” level of carbohydrate that works well, whereas full-strength Gatorade is too many carbs at once and spikes blood sugar.

Historically he’s carried one bottle each of water and Gatorade Endurance, but during the last couple weeks of his run across the US, he switched from Orange Mud’s double Hydraquiver to the single because it was cooler and lighter.

He also drank a protein shake at almost every stop, and sometimes I’d borrow a trick we picked up from hikers and add a spoonful of vegetable oil to bump up the calories. Bonus: it makes it creamier, too.

The Kitchen & The Pantry

“Y’all must eat at lots of great local spots!”

Um, no.

Don ate breakfast, lunch and all of his fuel breaks and bedtime snacks from our van supplies all day, every day, throughout the run. We mixed and matched our standard ingredients to keep food interesting enough to be edible.

In larger towns, sometimes we’d get an extra fast food breakfast sandwich, kid-size fast food burger, or keto-friendly salad to save for his lunch or dinner; and I’d usually stash an extra fast food sandwich or two for fuel breaks later that day or the next. If it’s McDonald’s, I might pick up an apple pie or an apple fritter for a later fuel break, since the carb count’s available. If we were near a chain restaurant at the end of the day, we often went with a fast food burger, a chef’s salad with chicken, or a small steak with veggie and potato. Fast food chains also had readily findable nutritional info, which made that an easy choice for a hot meal treat when the timing was right.

Mostly we avoid the interesting local places. They’re slow, they never have nutrition info, and the carb count on everything is always way, way more than we guess. Then we agonize over how much to dose, or correct, without causing a hypoglycemic catastrophe. Not worth the anxiety and it just causes too many problems.

One of the few exceptions was Jeff’s BBQ, a little food-truck style joint in the middle of nowhere, somewhere between Lavon and Josephine, TX. I was ahead on miles that day, it was Texas, it was BBQ, and it was fast! That’s their ordering counter in the main picture. But it was most definitely an exception.

What’s in the pantry?

We categorize our food into four categories. Here are some examples of what we packed. By the way, we eat literally almost none of these items at home except for cheese, peanut butter, Tasty Bite and the sugar-free condiments!

- Fast carbs: Oreos, Nutter-Butters, plain and peanut M&Ms. Great Value cookie butter. Fruit flavored whole milk yogurt. Full-fat Nido milk powder. Potato flakes for soup and tacos. No Paydays anymore, they’re too dry and chewy.

- Slow carbs: Costco hummus, fresh apples, single-serve cups of mandarin oranges, Tasty Bite Madras lentils from Costco, Barilla ready-to-eat pasta, instant grits, small fruit yogurt cups, Uncle Ben’s ready-to-eat brown rice, and Campbell’s chunky soups.

- Protein: Optimum Nutrition vanilla whey and chocolate whey powder from Costco (no sugar added), Ovaeasy egg crystals, boiled eggs from Costco or Walmart, single-serve chicken salad from Costco, single-serve string and stick cheese, Mountain House chicken, small plain yogurt cups, peanut butter, nuts, canned soup, full-fat Nido milk powder

- Add-Ins: ghee (no refrigeration needed), Splenda (ironic, right?), BBQ sauce, teriyaki sauce, Italian seasoning, curry powder, precooked chopped bacon, French’s fried onions, strawberry powder and banana powder for protein shakes, sugar-free ketchup and pickle relish, single-serve ranch dressing cups, vegetable oil for extra calories.

It’s very helpful to have options that don’t come with “built-in” fast carbs. Otherwise, too many foods end up off-limits if your BG runs high.

You’ll also notice a bias towards calorie-dense items like cookie butter and full-fat milk and yogurt. That’s because it’s a real challenge to eat 4000 calories/day. Every bite needs to deliver as many calories as possible.

Here’s two examples of how this works in practice:

- When we bring oatmeal, it’s the plain kind, not the sugary fruit-flavored kind. If Don needs fast carbs, we add a water-packed fruit cup plus a Honey Stinger packet or an Untapped maple syrup packet, both “real food” versions of runners gels.

- We get sugar-free whey powder for the same reason. If he’s high, we add only flavor extracts and Splenda, plus a shot of vegetable oil for extra calories (a backpacking tip we borrowed!). If he needs fast carbs, we add malted milk powder and Hershey’s Special Dark syrup, or freeze-dried fruit powders.

For Type 1 specifically, if you have a standard food item you rely on every day, consider having a low-carb version available so it’s easy to pivot if BGs are running high. For example, Don usually starts the day with a BG around 100, so regular cereal plus a protein shake works really well on run days. But if his sugar’s high at breakfast, we swap the sugary cereal for low-carb Cereal School/Schoolyard Snacks keto cereal.

For fast carbs, in our experience pre-portioned individually-wrapped packages with roughly similar carb counts are ideal. My favorites are the ones that actually print the nutritional label on each individually-wrapped package, not just on the box. That way you don’t have to stop and think about how many carbs Item A has vs Item B. It also keeps you from handling a family-size bag of food over and over with less-than-perfectly-clean hands. And the runner can take it with him and eat it while moving.

For example, Rice Krispie treats, the smallest fun-size packets of peanut and plain M&Ms, and two-cookie packs of Oreos and Nutter-Butters all come individually-wrapped and all run around 15 g each. Simple!

Fruit cups never have nutrition on the individual cups, so I write the number of grams on each cup with a Sharpie when we pack the van. You always think you’ll remember the numbers, but after a few weeks on the road, trust me…it’s a good idea to write them on the cups.

What’s in the kitchen?

Time spent cooking, eating and cleaning up is time that isn’t spent running or sleeping.

Be very, very realistic about how much food prep and cleanup is practical based on your needs, your crew, your physical setup (van, RV, SUV, etc.), and the time you have during the day.

Our goal is always food that is easy and fast to fix and eat, and minimizes cleanup in terms of both time and use of our on-board water.

Our cooking gear is intentionally limited. We’re in a van, not an RV, so we don’t have a dedicated kitchen. We pack a tiny amount of kitchen gear (one potholder, one sharp knife, one non-stick cooking spoon, a stove lighter, etc.) plus a very small Barocook chemical packet flameless cooking gadget and a Windburner campstove with one small pot and one small pan. We eat with plastic spoons out of disposable cups for food safety and speed reasons.

To minimize cleanup, we line the camp stove pan with foil before we cook in it. We only boil water in the pot. To minimize cleanup, we don’t cook or heat food directly in it. We cover the Barocook pan with a small piece of foil or place foods in a Ziploc that then goes in the Barocook pan.

Definitely not fancy, and not very environmentally friendly. But it saves time and conserves our on-board water.

Tech and Gear

Cronometer food tracking app – We set up a Custom Food List with all of our pantry items and configured custom nutritional targets. The app also has a huge database of common foods plus brand-name and restaurant foods.

Key point – this is not about surgical precision. If Don eats a random cinnamon roll from a convenience store, we just pick something that looks similar in Cronometer. We don’t track non-caloric liquids like water or diet soda at all and we totally ignore Strava’s calorie count.

We track fuel breaks throughout the day. That way, if Don’s falling short on protein or calories, we can make mid-course corrections. That’s especially important on days when media calls or traffic or weather or visitors or unexpected problems distract you and blow up your usual routine. Those are the times when he’s most at risk for falling short on calories, which greatly increases the risk of a hard low later on.

Blender Bottle & its brush—Absolute must-have for protein shakes.

Mini-scale—doesn’t see a ton of use, but super-handy for estimating carbs on unfamiliar items.

Small rectangular storage containers—for fast dispensing of bulk items like protein powder or powdered milk. We used to use Nalgene bottles, but the openings were too small and the bottles had to be refilled too often.

MSR Windburner camp stove, small pot, small pan—an upgrade after we couldn’t light our Soto Amicus stove in Iowa’s 50-mph wind gusts! Used to boil water for things like precooked rice, precooked pasta, microwave mac and cheese, and rehydrating Mountain House freeze-dried chicken or freeze-dried veggies, scrambled Ovaeasy eggs and quesadillas. For safety reasons, we also use an aluminum windscreen around the designated cooking area in the van.

Barocook flameless heat-pack cooking system—handy for heating things like canned soup, shelf-stable entrees like Tasty Bite, leftover restaurant food, or convenience-store pizza slices.

Dometic fridge powered by LiFePo battery charged by van’s engine—stays at 40F so we can store insulin and pack perishable food like boiled eggs and chicken salad. We added a Thermoworks temperature alarm for the USA trip.

Don’s Personal Guidelines for Ultrarunning with Type 1 Diabetes

For the U.S. run, covering 30-38 miles in about 10-11 hours a day, we followed these rough guidelines based on Don’s lived experience. Everyone’s different, so your personal guidelines are probably going to be different too.

Insulin Pump Settings

He started the run with his Tandem t:slim insulin pump + Dexcom G6 with only BasalIQ enabled. ControlIQ had just become available so there wasn’t enough time to get it installed and get comfortable with it before the run was underway.

After the first COVID pause, he installed ControlIQ and by the time of the third and final restart in March 2021, felt pretty comfortable with it.

As most T1s who exercise already know, automatic boluses are showstoppers for this kind of ongoing activity. So for the first week or so, he kept the Tandem in exercise mode, switching to Sleep mode overnight, and it worked fairly well.

Starting the second week, persistent lows trends became more of an issue. We banged on it for about a week, dropping correction factors and carb ratios by 20-40%, but the automatic boluses were still a problem.

At that point he switched to Sleep mode 24/7 and that was the Goldilocks moment. Sleep aims for a lower target than normal or exercise mode, but gets there exclusively through basal adjustments, no boluses. It worked very well in combination with the already-lowered correction factors and carb ratios.

Pro tip: remember to turn off your automatic sleep schedule if you go this route. The first day we tried it, he started running at 7 AM in Sleep mode—which automatically turned itself off at 8 AM, dammit! We didn’t realize until he had to treat a low a couple hours later that our Big Idea needed just that little tweak.

Blood sugar >250: 30% to 80% of usual correction bolus depending on specific circumstances and personal experience with insulin sensitivity in these conditions, distances, weather, etc.

Don’t let IOB get away from you. This is not the time to rage-bolus. If high blood sugars persist despite correction boluses and there’s no obvious reason (like extreme heat, pain or brushes with death), change your infuser and tubing. If it still doesn’t help, dose with a syringe from a different bottle of insulin just to confirm insulin is still OK.

Emphasize high-protein, high-fat, minimal-carb foods and plenty of liquids until it’s back below 200.

If ketones are fine and you’ve done all the above, in our experience persistent highs are just a result of the overall physiological stress. Our strategy is to keep going, but dial everything down a notch—if you’re in pain from blisters or tendonitis or whatever, take the time to address the pain; if it’s hot, deploy all your cooldown techniques; slow down your pace; trim your daily mileage; get your planned sleep; make absolutely sure you’re eating and dosing and hydrating.

And if there’s anything you know will help your mindset, do it: music during a fueling break, a 15-minute eyes-closed break, whatever.

Not just physical stress but psychological stress can knock your sugars for a loop, sending them persistently and stubbornly high, so that “dosing down”, the normal recommendation, isn’t effective. Your body’s busy dumping glycogen into your bloodstream and flooding your system with cortisol so you can “escape the cheetah.” When what’s going on around you starts creating stress hormones, it’s called sympathetic nervous system overload. Soldiers get it. So do air traffic controllers and people in other high stress jobs. And it sucks, because it can send you into a spiral of dosing and not eating, and meanwhile you’re not really treating the actual problem.

Blood sugar 200-225: 20% to 30% of usual correction bolus depending on specific circumstances.

Go with high-protein, high-fat, minimal-carb foods until it’s back in a normal range. This usually translates to one fuel break without fast carbs, then we’re back to normal fueling. For example, this is a situation where I might add a spoonful of vegetable oil to a protein shake to get more calories without carbs.

Sometimes Don’s sugar runs high if he’s fueled normally but ends up having to walk more due to traffic, or because he stopped briefly to visit with other T1s or local media. Everyone with Type 1 knows that even a 15-20 minute stop can spike blood sugar fast when you just downed 45-60 grams of fast carbs and no insulin!

If BG doesn’t drop significantly within 1-2 low-carb fuel breaks, it’s almost always either the infuser and tubing, or insulin ruined by very hot or freezing temps.

Blood sugar 130-170: This is what we consider normal and desirable during the day’s running. Sugars can drop really fast after a few days of daily running, so we don’t want to run it at or below 100 because a hard low on a road shoulder in the middle of traffic or next to a sharp dropoff or gully is a really bad idea.

Fuel breaks in this range always include protein and fat. At the lower end of the BG range, they also include 30 grams or so of fast carbs. For higher BGs, they’d include around 8 g of fast carbs and perhaps a slow carb like hummus.

Blood sugar 90-120: In this range, assuming no IOB, we throw 45-60 grams of fast carbs at it, plus fat and protein. IOB and the overall trend—flat, trending up, trending down—plus a general feel for current insulin sensitivity determine exactly what we go with.

Blood sugar < 80: The goal here is to get back up as fast as possible with the fastest carbs available, because Don won’t start running again until it’s trending up. “Trending up” is defined as a finger-stick test that shows 85 or so, plus Dexcom showing an angled-up arrow.

Run-Specific Strategies for Lows

The first thing Don does when BGs are below 80 or so is to drink at least one Reli-On liquid glucose ‘shot’, two if it’s in the 70s or lower, or he has 2 units or more of IOB. We do use the Control-IQ IOB number and although it’s vaguely-defined, it has still worked well for this purpose.

(I’m mentioning Reli-On specifically because it’s about half the price of other lliquid glucose ‘shots’.)

Liquid glucose shots are the fastest carb we carry. After Odessa, especially if Don has IOB, we never ever treat lows with gels or food first, because they’re not absorbed nearly as quickly. If you go with gels, remember that you need to wash them down with liquid for fastest absorption.

Then he eats the same fuel he’d eat if his sugar were low-normal: another 45-60 grams of carbs, plus protein and fat.

Don also carries a couple of glucose ‘shots’ in his running pack while he’s actually running, in addition to gels and/or chews as backup. A single-step liquid glucose ‘shot’ that can be slammed down is faster and easier if you’re standing on a steep road shoulder trying to think straight as traffic whizzes past.

Thoughts about Persistent Highs

Don hasn’t typically seen persistent highs until late in any given run. By the final weeks of the U.S. run, when we were banking miles almost every day so we’d have lighter mileage days near the finish, his BGs were often over 200 even though he was dosing consistently and avoiding fast carbs. However, thanks to Control-IQ, they generally stayed in the low 200s rather than creeping up and up.

The high pattern is something we’ve seen before, and we attribute it to the accumulated physiological stress. The fact that his TDD crept up from 30 units/day to 45 units/day by the time we had reached the Atlantic coast finish line seems to support that hypothesis.

Our theory is that lowering daily miles, getting more sleep, and planning more zero days would weaken this pattern, and that’s consistent with what we’ve observed across all the runs.

Miscellaneous Tips

Think through likely scenarios. What if you’re over 200? 300? What if you’re at 120 but you have 2 units on board? What if you normally eat very-low-carb and you figured you’d do that during your run, but now your BGs are routinely dropping into the 40s?

While even the best plans won’t always work in practice, it’s still smart to anticipate obvious scenarios. Don’t be us in Kansas, with nothing but fruit yogurt.

Plan to do a lot of fingerstick tests. It’s not uncommon for Dexie to lag by 60-70 points or even more when BGs are changing rapidly. That results in the Tandem pump dosing in the background via Control-IQ to correct a high-ish BG when the actual fingerstick reading is, say, 100.

Change Dexcom Follow app settings to their most protective. At home, we normally keep the low alarm threshold in Dexcom’s Follow app at 60, the lowest setting. But during events, we raise it to 100 because BGs can drop so fast. You want your support team to know what’s going on with enough advance notice to make good decisions.

For example, if Don is 2 miles away and I see he’s at 100 with a flat arrow, if I know he doesn’t have much IOB and he had 45 grams at the last fuel break, I’d probably keep an eye on the Follow app, check his speed via the Inreach tracker, and assuming all that data stays consistent, just wait for him at our prearranged meetup. On the other hand, if I see on the tracker that he’s slowed way down, and the Dexcom thinks he’s at 80 with an angled-down arrow, I’ll drive back.

Watch out for “autopilot” mode. No, that’s not a pump setting! When you’re deeply fatigued, it’s easy to drift into “autopilot” mode—to fall back into everyday habits that don’t serve you well during the run. For example, the reason Don didn’t eat most of the carbs on his plate in Odessa was because he doesn’t eat lots of carbs at home. He dosed using his at-home carb ratios, instead of the less-aggressive ratios he uses during runs. If he had been less tired, he wouldn’t have done that, and I wasn’t paying enough attention to help connect the dots.

TDD (total daily dose) trends are a great reality check. When you’re slogging out the miles, it’s easy to fall into the trap of repeatedly adjusting for high BGs and never quite grasping that you’ve been doing this all day and it hasn’t helped.

Seeing that you’ve already gotten almost 100% of your typical TDD by 10 AM can be a wake-up call that snaps everything back into focus and push you to stop long enough to figure out sensible next steps like changing an infuser, tubing or your bottle of insulin.

We highly recommend a fingerstick ketone meter. If you’re persistently high, this lets you quickly rule out the possibility of bad insulin or get early warning of a potential crisis.

It’s also important if you’re Type 1 and taking SGLT2 meds like Invokana. SGLT2 meds in combination with lower insulin dosage due to exercise; dehydration due to exercise; and/or low-carb diets is a risk factor for DKA in folks with Type 1 diabetes. If you take one of these meds, daily ketone tests during your event are probably smart since DKA in this specific situation can develop very quickly even when blood sugars are normal or normal-ish.