Your donations help T1Determined #keepgoing.

Don Muchow

I’ve been a type 1 diabetic since May of 1972, and was told by my elementary school teachers that I didn’t have to go to gym class. I followed that “sage advice” until 2004, when I began to have complications. Since then, I’ve been making up for lost time.

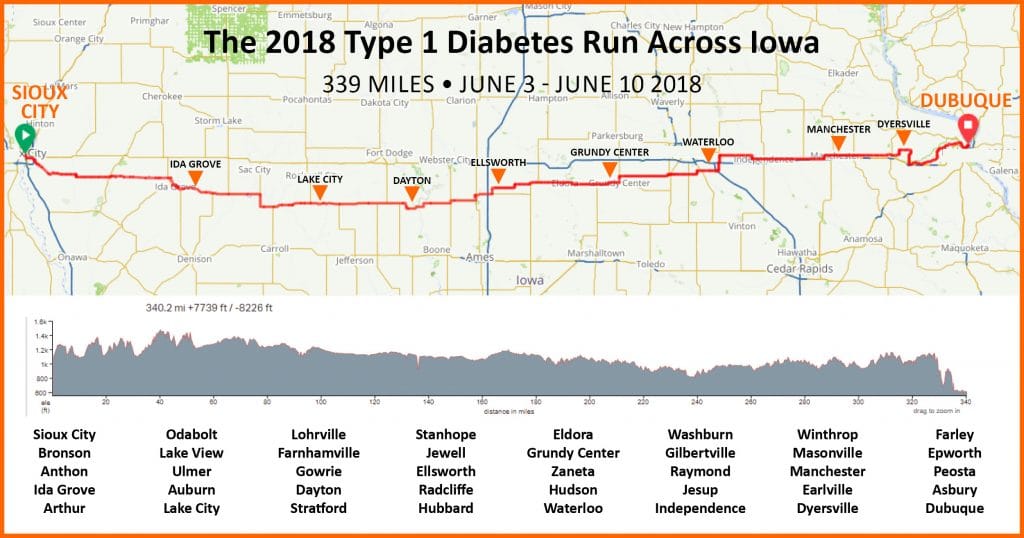

In the last 12 months I’ve age-grouped in a quadruple marathon, finished my first full Ironman, run my first 100-mile ultra, and completed my first 200+ mile super-ultramarathon. In June of 2018 I completed a 339-mile solo run of Relay Iowa (Sioux City to Dubuque); in 2019, I completed an 851-mile run across Texas; and in 2020 I hope to become the oldest type 1 to complete a solo run across the continental U.S. (Doug Masiuk was the first).

This is my story, and hopefully, that’s just the beginning of it.

1972: “Rx: Avoid exercise”

First, let me start by saying that I haven’t always been active.

First, let me start by saying that I haven’t always been active.

I don’t consider that entirely my fault, either.

As I mentioned above, in a misplaced effort to protect me from experiencing low blood sugars during exercise, my doctors and teachers in 1972, the year I was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, told me to avoid exercise.

Yeah, you read that right.

My docs and my gym teacher told me to avoid exercise.

1982: I get my first glucose meter

For 10 years, I was just guessing at what to eat and how much insulin to get for it. That’s all I COULD do. Glucose meters weren’t commercially available yet, and while urine tests had progressed from test tubes to strips, they still only hinted at just how badly I had screwed up the food-insulin balance.

Yeah, THIS brick.

In 1982, I got an Ames Glucometer, literally the size of a brick. You had to clean off the sensor window with a Q-tip and alcohol, and it wanted a “hanging drop” of blood and had a 60-second wait for results. It cost $300 (equivalent of $1200 in today’s dollars), and required insurance. Not health insurance–insurance against failure of the meter, because it was so expensive!

FINALLY I could tell what my blood sugar was in the moment. But there still wasn’t much I could do about it.

Minimed didn’t introduce its first widely-available insulin pumps until 3 years later, and at that point, in terms of control, I was little better off with the “brick” than I had been before. I got one shot of NPH — long-acting insulin each day, plus separate meal shots of Regular insulin. I had no idea how to make small boluses to correct blood sugar, and terms like “insulin sensitivity factor” or “insulin-to-carb ratio” were nowhere to be heard — at least not by me.

I was in college now, and literally pissing away my life. Lows, highs, my control was horrible, and it affected my alertness and ability to focus, hurt my grades, and made things generally miserable.

2003: The exercise chickens come home to roost

With the Glucometer, trying for tighter control and treating all those lows added up to extra calories — quickly. My job sucked up most of the hours in my day, and even if I had the time to do something active, I was scared of going low. By the early 2000’s, I was fifty pounds overweight, and doing nothing about it — except worrying.

With the Glucometer, trying for tighter control and treating all those lows added up to extra calories — quickly. My job sucked up most of the hours in my day, and even if I had the time to do something active, I was scared of going low. By the early 2000’s, I was fifty pounds overweight, and doing nothing about it — except worrying.

I couldn’t see past my belly button. I could barely even see my feet. I wasn’t using an insulin pump, and was still basically on the same sort of MDI, NPH+Regular, sliding scale, eat-the-same-thing-every-day insulin regime my docs had me on in 1972. Sure, there were fancier insulins now, and my dose guesses were a little better, but I began to wonder just how long I could keep things up before complications set in.

And I wasn’t the only one worrying. My wife Leslie was concerned as well, and I knew it. In fact, it kind of paralyzed me that she was concerned enough to let me know. Usually she’s pretty good at being the calm one in the midst of the storm. It didn’t help that I had been quietly panicking, trying to run in place in hotel rooms and practice deadlifting my luggage while simultaneously working to get software demos up and running before the next day’s customer meeting.

Ironically, now that I was finally anxious enough about doing something, I had no predictable time in my schedule to do it.

2004: The breaking point

Leslie and I had already decided to throw out our big plates and eat off saucers, consciously try to avoid excess carbohydrates, and work out 20 minutes twice a week in the little gym in our loft complex. We did it when I wasn’t on the road, and we decided we’d take whatever results we could get. If it was too hard, we’d dial back the effort until it wasn’t.

For the first time in my life, I started feeling a little more confidence about diabetes control.

I had heard wondrous stories about people achieving greater control through the ability to give themselves small boluses, as well as knowing the amount of insulin on board at all times, AND the pump actually figured that in and adjusted the dosage accordingly.

One week, while Leslie was away on business, I called my doc and a Medtronic rep and asked to be put on an insulin pump. When she got back home, I was a proud “pumper.”

Later that year, I also proudly signed up for my first 5K, the Dallas YMCA Turkey Trot.

And shortly thereafter, I learned from my retina specialist that I needed laser surgery to stop bleeding and lipid leakage the back of my eye that threatened my retina.

Thirty-two years after diagnosis, I was experiencing serious complications, just when I had decided to do something to avoid them.

I promised myself then and there that “if I could just get a do-over,” I’d do whatever I could to maintain tight control, stay physically active, and make the best of what I still had.

That November, Leslie and I ran the Turkey Trot together. I still have my finisher shirt and medal. It’s one of the things I’m proudest of doing.

2008: I meet other diabetic runners

Somewhere along the way, I realized that with running, you can just keep training until you can do longer distances.

Somewhere along the way, I realized that with running, you can just keep training until you can do longer distances.

In January of 2008, I met Missy Snider, a fellow Type 1 runner in the Dallas-Ft. Worth area, who was interested in meeting and running and exchanging tips with other Type 1s in the metroplex. That same year, I met Julie Kuehn and Carol Ezell, fellow Type 1s who had already run longer races. I met Jeff Kilarski, DFW captain of the American Diabetes Association’s “house” cycling team, Team Red.

I eagerly pestered them all for training tips, fueling tips, and tips on how to adjust my pump and test during races, and kept going.

2009-2013: From half marathons to ultras

5 years later, in 2009. I ran my first half marathon, the Texas Half. The high that day was 28 degrees. I was super happy that the continuous glucose monitor I had taped to my belly was warm enough to get a BG reading, since my finger-stick meter shut down due to the cold.

5 years later, in 2009. I ran my first half marathon, the Texas Half. The high that day was 28 degrees. I was super happy that the continuous glucose monitor I had taped to my belly was warm enough to get a BG reading, since my finger-stick meter shut down due to the cold.

Two years later, I completed my first full marathon, the Dallas Marathon in 2011; and my first 50K run, the Cowtown Ultra, in 2013.

I have to tell you, I felt pretty darn proud to have run more than 26.2 miles.

It was the first time I didn’t actually avoid using the term “diabetic athlete” to describe myself.

2014: I get hooked on ultras and triathlons

Truth be told, I was probably already hooked by 2013. I was feeling pretty confident about what I could do, and a diabetic friend of mine suggested — probably just giving me a hard time — that I should train to do an Ironman event.

Except for one thing: I couldn’t really swim. Since that’s one of the 3 required Ironman sports, suddenly I felt like 5K Don again: a total rube, completely ignorant, and some kind of fake.

I searched for a swim coach who would understand my fears about going low in the water, and would be willing to watch for signs that I needed to stop and get a runner’s gel. I’m always afraid that personal trainers, coaches and the like will just push, push, push without realizing that often, what looks like low effort is really low blood sugar.

I never actually found a swim coach who knew diabetes. But I found a good listener: a swim coach named Bryan Mineo. Bryan’s the kind of guy who watches what you do, and rather than criticizing it, asks at the end: “how did that feel?” “Did that work for you?” He’s more like an extremely skilled, knowledgeable, swimming psychotherapist. Bryan let me do all the stupid stuff until I had run out of ways to do it. He was clever to NOT offer his advice until I absolutely craved it and understood its value.

I trained with Bryan for 10 weeks, plus a fraction of somebody else’s swim training that was given to me when the other swimmer moved away. I got good enough to actually complete the Cooper Sprint Triathlon in 2013 or 2014. My 300-meter time was 16 and a half minutes — incredibly slow. These days I could swim that distance in 4:30. I think maybe I backstroked the last 50 meters. I know I was relieved to get out.

After that, Robin, another diabetic athlete and friend introduced me to swimming in open water — how to sight, how to adapt to current and waves, and how to locate and swim for shore when I felt like all I had left was another 50 meters. Another yet another Type 1 diabetic athlete friend, Michelle (herself an Ironman finisher), taught me to swim confidently. And even though she accidentally on purpose lied to me about how far the buoy was, by then I “got it.”

The only things holding me back, I learned, were information and the confidence to act on it despite not knowing everything.

2015: My first (successful) half Ironman

OK, I didn’t exactly say that right. My first ATTEMPT at a half iron was in 2014. Barely a year after I had learned how to really swim and not just splash around.

OK, I didn’t exactly say that right. My first ATTEMPT at a half iron was in 2014. Barely a year after I had learned how to really swim and not just splash around.

Doing pool swims and practicing in local lakes taught me quite a bit. There was hardly a weekend I wasn’t at the lake with a couple of other diabetic swimming buddies (I’m really big on the “don’t do this alone” angle). I trained until I couldn’t stand the temperatures any more, in mid-December, with a thermal cap and neoprene booties. I was lucky I didn’t get hypothermia.

I signed up for Ironman 70.3 Galveston, in April.

I caught an upper respiratory infection 3 weeks before the race, tried to train right through it, and was still popping menthol lozenges up until the day before the race.

On race day, I came out of the swim with 15 minutes to spare.

Then I blew a tire on mile 6 of the bike and never made up the time. DNF.

I took advantage of the next year to train a little smarter, a little harder, and focus on keeping my break times short. I signed up for Ironman Texas 70.3 Austin and completed it in 7 hours 39 minutes (time in picture shows time since starting gun). The group of Type 1 diabetic athletes I had helped get together in 2008 met me at the finish line.

I swear there was something in my eye.

2017: The year of attempting everything

In 2016, I signed up and failed to finish a 140.6 triathlon, HITS Waconia, in Minnesota. It rained all week, and the day of the race, the waves were so tall and choppy on the lake that one of the two emergency watercraft on the lake capsized, and the other could not see swimmers through the fog and waves. I turned around after 400 meters, swam to shore, and informed the race staff that I was DNF’ing myself and going home.

It pays to know when to quit. I had learned some incredible lessons about insulin sensitivity, insulin resistance, stress, fueling for longer distance, and training for an event that required both muscular strength and endurance in the same event. And I had learned at Waconia that there is never any shame in knowing when to say enough is enough.

And quitting doesn’t stop you from going back and trying again.

I had another season to train, and I put every spare moment I had into making sure I trained for conditions and could finish Ironman Texas 140.6 The Woodlands. I felt like this event was made for me: well over 80 miles of the 112-mile bike course were on closed lanes of the beautifully-paved Hardy Tollway outside of Houston. The swim was in a shallow, calm lake that fed into an even shallower channel similar to San Antonio’s Riverwalk. The transition between swim and bike, bike and run was set up for maximum efficiency. Great spectator energy and involvement, with a “Hollywood” finish in an expensive downtown retail district.

During my training, I fretted constantly about whether I’d finish the bike on time. I trained in wind and on hills, but with traffic lights, it was hard to tell if it really was taking me more than 8 and a half hours to ride 112 miles. My wife and I practiced handing off empty water bottles and picking up full ones. I tried all different types of fuel to determine which ones wouldn’t spike my blood sugar too fast on the bike but would kick in fast enough on the run. We worked on every little detail, and I trained until I ran out of good weather to train in.

I completed Ironman Texas in 15 hours, 20 minutes, and 34 seconds, a full 90 minutes faster than I had predicted from my training.

I credit most of this to the fact that I had already signed up for my first 100-mile run, the Honey Badger 100 Mile Ultra Road Race in the first week of July, around the time of my 56th birthday, and my first 200+ mile solo run in October.

July 2017: HB100, or How to Screw up a Good 100 Miler in Just 50 Miles–Then Save It

Like I said, there’s a point where you should know when to quit.

Like I said, there’s a point where you should know when to quit.

I might have missed that point in July of 2017.

The Honey Badger 100 Mile Ultra Road Race was held just outside of Wichita Kansas, when daytime temps are in the 100s and the sun beats on you like the world’s worst boss.

That, no restrooms for the first 50 miles, and the fact that you had to cover 53 miles within a 14-hour cutoff, were constantly on my mind. I pushed my pace early, staying with the other runners, including Arnold Begay, a guy from Oklahoma who had run Badwater and seemed to know a thing or two about running in the heat. I walked when they walked, and ran when they ran.

And then, 47 miles and around 12 hours in, the balls of my feet started hurting. I probably should have stopped and changed shoes and socks, but I was intent on making it to the next checkpoint, letting the race director know I was on pace to make the 53-mile cutoff before my 14 hours were up. I knew I had been walking a bit more because it hurt to run. Now, it hurt to walk, too. Just 3 miles short of the cutoff, I stopped at the only gas station within 100 miles and Leslie treated the blisters — fortunately unbroken — and taped the unblistered parts.

I made it to the cutoff with 90 minutes to spare, just like Ironman Texas. I had covered more than half the total miles with well over half the remaining time before the 36-hour final cutoff remaining. I ate the best mashed potatoes and chicken and rice soup in the history of man and rolled back out again, as night fell over the cornfields and wind turbines.

Then my sugar started climbing up. At first, I thought it was the food, so I laid off my normal fueling pattern for a little bit to let the food I had already eaten do its thing.

It kept going up. Somewhere in the middle of the night, Leslie and I figured out it was due to the extreme pain in my feet, probably exacerbated by the physical stress of pushing so hard to make sure I hit the 53-mile cutoff.

But, I couldn’t keep not eating if I wanted to keep going. So even though I was in the mid-200s by that point, I got more food. That actually helped lower my blood sugar a bit (be sure to read about stress, blood sugar, and ultra endurance).

I covered another thirty miles overnight. My sugars stayed stable for most of that time until when an angry driver in a white Ford F-250 pickup truck deliberately ran several of us runners off the road. I had to dive headfirst into a culvert, and — worst of all — climb out of the ditch on severely blistered feet.

The combination of having run 17 or 18 solid hours in 95-100 degree temps on blistered feet, then having to jump for my life into a ditch, really jacked my sugar up.

The weirdest part of it was that I could not feel any adrenaline rush. My body was already pumping stress hormones like crazy.

The night dragged on. After what seemed like an eternity, the sun was coming up. I was at mile 85, succumbing to slight perceptual miscues such as mistaking the sounds of oil drilling equipment and windmills for nonexistent runners behind me (I was actually 2nd from last at this point, as 3 runners behind me had bailed), but it had been night, and cooler, and while I felt sleep deprived, it wasn’t any worse than pulling an all-nighter in college or preparing software demos on my laptop at 3 in the morning.

You can see the sun peeking over the corn that morning in this photo.

Minutes later, the temperatures started rising. By 8:30 AM it was in the 90s, and I still had 15 miles to go.

As soon as the heat kicked in, my sugar rocketed up, from the mid-200s to 550 mg/dl. Not a number I could remember ever even seeing before.

I sat down with Leslie to figure out what to do. We knew the standard advice would be to stop right away. But other than my feet, and general fatigue, I actually felt pretty good. I had been avoiding insulin, because I was afraid I’d be fighting lows after staying on the move for so long. We changed that decision on the spot. I treated the high and switched to walking the last 5 miles, saving maybe 100 yards to run to the finish line, and we agreed that if I experienced any further issues — no matter how small — I’d quit.

This is a decision you can’t — or shouldn’t — make on your own, because after running this long, in the heat, in pain, without sleep and with a BG of 500+, you’re too screwed up in the head to count on yourself to think straight.

It’s based on a principle I learned from ultra endurance swimmer Lynne Cox‘s book: it takes the whole team–the runner, the crew chief, and any pacers you might have–to agree to continue when conditions get challenging. But it only takes ONE person — the athlete, or a crew member of pacer, to call it off. We were thatclose to calling it off.

I finished in 32 hours, 14 minutes, and 20 seconds, about 2 hours longer than I thought I’d take. But I was happy.

In those last 5 miles, I ate a little and drank a lot. And my sugar dropped 200 points. Lesson learned: physical stress and severe pain can raise blood sugar. When that happens, dose for the high — and continue fueling for the activity.

October 2017: Capital to Coast Solo Run

I learned some valuable lessons from Honey Badger, principally that eating whether you want to or not is critical, and that sleep is important, but that you can push it off for a little while.

I learned some valuable lessons from Honey Badger, principally that eating whether you want to or not is critical, and that sleep is important, but that you can push it off for a little while.

The 223-mile Capital to Coast Relay is one of very few relay events that allows solo runners as official entrants. In fact, I know of only one other, the 260-mile Run Across Georgia. But Georgia has a fixed start time and an expected finish-by time that would require some pretty aggressive running for a 56-year-old diabetic guy (Hint: it’s important to remember that you’re not Superman, and to work with what you have). After that you’re talking about the odd 200+ miler such as the Last Annual Vol State 500K (314 miles across Tennessee in the summer).

Having run C2C as a relay runner on various “legs” of the relay, I was familiar with the course. In May of 2017 Leslie and I scouted the route and I ran 100 miles of it, including about 70 miles from Buda, TX to Seguin, and from Sinton, TX to Portland, just outside of Corpus Christi, where the finish line would be in October. In August, during the hottest part of Texas summer, I added 40-mile loops on a gravel trail between Weatherford and Mineral Wells, TX to my training plus dry and steam sauna sessions.

I learned quickly from that during the hot Texas spring and hotter summer, real desert running gear, including a wide-brimmed hat with a “Kalahari” flap, and a double-layered vented white nylon long-sleeve desert running shirt are essential. When ambient temperatures are above body temperature, you can’t evaporate sweat. You have to rely on your own body heat rising inside your shirt and causing a “heat chimney.” Convection drives cooler air in through mesh underarms and keeps you relatively cool.

I learned that at night, illuminated vests attract cars rather than deterring them from hitting you on the side of the road. I learned to step quickly off the road when challenged by rush hour traffic on narrow two-lane roads at 6 AM.

I learned that even if you tape your feet, you have to change shoes regularly because your feet swell. I learned that you can even tape your feet well enough that they won’t blister for 160 miles, and when they do, it will be relatively minor.

The two major things I DIDN’T learn until C2C were:

- You have no idea how long your little breaks take — but it’s longer than you think.

- If you push past your limit on sleep, you WILL hallucinate, or at least mis-perceive what you’re seeing.

Unfortunately, these two are related. If you run long on breaks, you will have to either manage breaks more aggressively — literally limiting them to 3 minutes, regardless of whether you’re done resting, eating, or using the restroom on the side of the road, or run short on sleep. Anything else and you’re not going to finish.

If you run low on sleep, you will hallucinate, and your judgment about your blood sugars will go to hell in a handbasket.

Despite meticulous planning, my timeline broke down a bit. “Fast” breaks to give my feet a quick rest or to test my sugar ran 5 minutes every time for the first couple of days. Meal breaks dragged on. Hotel stops for 4.5 sleep breaks turned into 5 or 5.5 hour breaks simply because of the inefficiency of the check-in process.

By the middle of the third day, already low on sleep due to aggressive planning of short sleep breaks, we knew we weren’t going to finish on time unless we skipped the last sleep break.

Remember my rule about “everyone’s a go, anyone’s a stop”?

Well, we ALL agreed to skip that last sleep break. The crew could, after all, sleep in the chase vehicle, and did from time to time. We rotated everyone in the crew onto the road as pacers to keep me sane and attentive. My crew kept an eye on whether I could still think rationally enough, with enough mental clarity, to safely keep going.

Somewhere around mile 180 I hallucinated that a fire ant mound was first a guardrail, then a packing box. On leg 30 of 36, 186 miles into the 223-mile race, I thought my wife had suddenly said “devilish” to me — and had a brief, crew-imposed nap.

With 43 miles to go, we calculated that if I could take a 30 minute nap and still average a 4 mph pace while walking–including breaks (I didn’t have much energy to run any more), I could make it to the causeway into Corpus before sunset–an unofficial cutoff for safety reasons–and finish the race.

At about that time, I finally started seeing relay runners catch up to me. They had been following my progress and offered encouragement.

I was emotionally overwhelmed by the outpouring of support. So I guess that makes 3 things I didn’t learn until C2C, the last one being that above 200 miles, you get emotionally “elastic.” Little things like chocolate, or a pebble in your shoe, turn into big things. You’re either having the Best Day of Your Life, or Life Sucks And We’re All Gonna Die.

I walked…and walked… and walked.

A few miles before the finish line, my old relay team — all with Type 1 diabetes — caught up with me as they finished their relay legs, and stayed with me until the last few steps.

I hallucinated some more, including the location of my crew near the finish line. I thought they were right with me, and as the sun set, I bolted to the finish, leaving them behind.

My crew forgave me, but that was… well, crushing, just when we were all kind of fragile.

We finished in 88 hours, 11 minutes, and 27 seconds, around 7:20 PM, about 20 minutes over my anticipated finish time.

I emphasize WE because there’s absolutely no way I could have done this without my crew.

Leslie Barker of the Dallas Morning News wrote more eloquently than I can about the Capital to Coast run.

Recovery and the road ahead

Still learning…

Still learning…

It took me even longer to recover from C2C than it did to recover from Honey Badger. While I felt voraciously hungry for a solid week, slept late and took long naps for a week after that, and my blisters took the same 3 weeks to heal, my sugars ran high for almost a month afterwards.

There aren’t that many super-ultra distance type 1 runners out there, but I’ve heard from others with similar experiences. Most of those folks, including myself, lay off the high-carb diets after the first big recovery meal. All I can figure is that there’s a lot going on to rebuild not just energy stores and muscle, but reduce inflammation and restore a general resiliency, that takes a lot of time. I imagine stress hormones are still busy. In fact, based on my immunologist’s suggestion to continue doubling my Allegra for a week afterwards, I’m inclined to think so.

What was a little troubling were the repeated dreams for a couple solid weeks that I was still running, and hadn’t finished the race. I suppose the mind is taking out the garbage, or something similar. I really don’t know.

Iowa and beyond

As I look ahead to running the 339-mile Relay Iowa as a solo runner in June 2018 (update: I finished this race on June 10th, 2018, after 7 days, 17 hours, and 8 minutes), and running across Texas from El Paso to Texarkana in 2019 — and hopefully the continental US in 2020, I have to think not just about the normal diabetes and exercise things, but about the weird effects of stress, sleep deprivation, and exhaustion. Those have a very real effect on blood sugars, and there’s not a lot of data out there as to how to deal with it. I look to experts like Doug Masiuk (first Type 1 to run across the US), Ayden Byle and Sebastian Sasseville (the first and second T1D’s to cross Canada), and Joel Livesey (first Type 1 to run the Badwater 135 ultra in Death Valley, CA in July) for insight.

I may just have to go and figure things out for myself. And I’m all right with that.

I realize now that I’ve had way more than my “do-over.” Running ultras has been my journey to redemption, better control, and a feeling of empowerment that a lot of us dealing with type 1 diabetes feel has been taken from us. Running has taught me that it’s not about how fast you go, or how far, but what you learn from getting there, and whether you can learn it in time to save your own life.

No matter what happens now, I’m grateful to have been given the chance.

Don Muchow, 12/27/2017

Hey, Don,

Sebastien Sasseville is an inspiration and a good friend of mine, but Ayden Byle is the first type 1 diabetic to run across Canada, the first to cross the continent of North America, I guess. He did it in 1998.

http://www.positivehealth.com/article/diabetes/ayden-byle-canadian-diabetic-athlete

Did not know that! Thanks for the update, I’ve added him.