Your donations help T1Determined #keepgoing.

Type 1 Diabetic Ultrarunning Tips for 100° & Higher Summer Temperatures: What I’ve Learned

“It’s not the heat, it’s the stupidity.”

— Type 1 diabetic Ironman, endurance cyclist, and ultrarunner Isabella Arjona, Houston, TX

I live and train in Dallas, TX for cross-state and transcontinental runs plus triathlons.

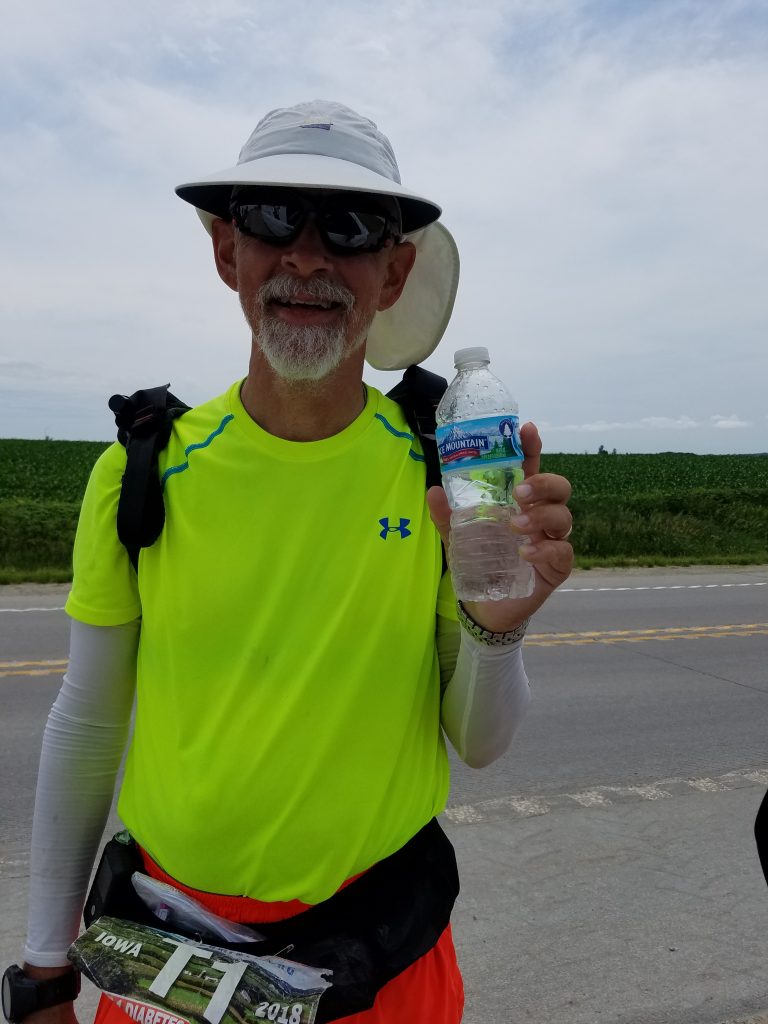

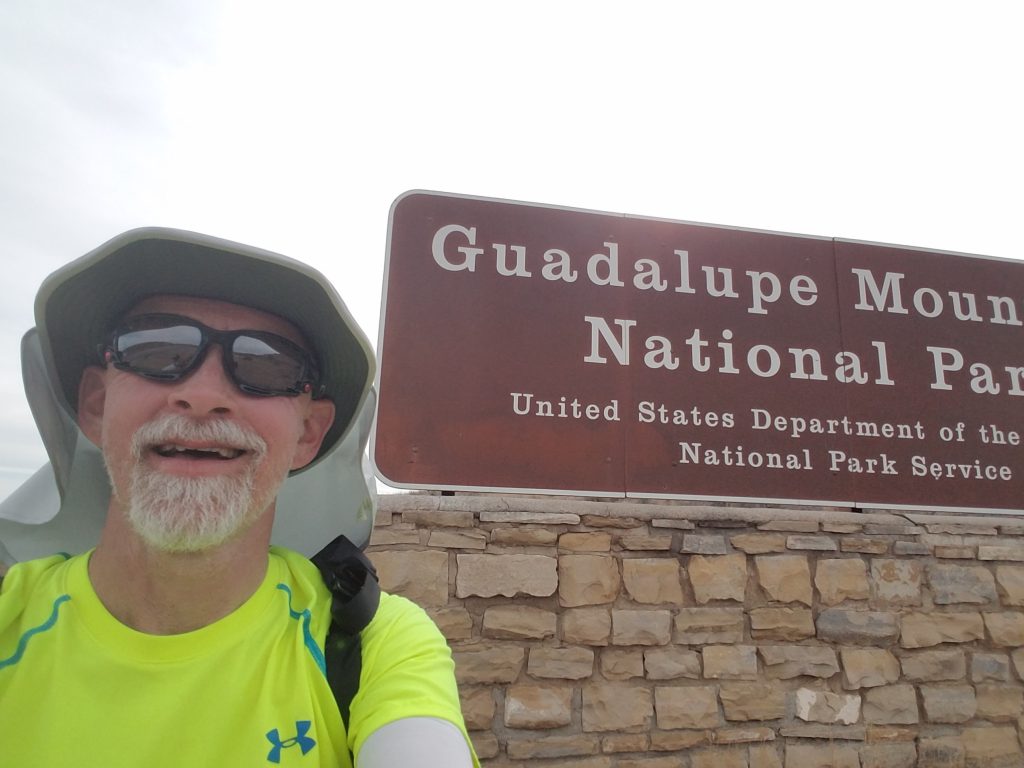

I ran 2845 miles across the USA in 2020-2021, watching COVID-19 related delays push my finish time later and later in the year. I ran 850 miles across Texas in 2019. 339 miles across Iowa in rhe summer of 2018. 223 miles from Austin to Corpus Christi, TX in 2017. 100 miles at the Honey Badger Road ultra in July, in Kansas. I finished Ironman Texas a couple years back plus a lot of other runs, rides and tris, all in very hot weather.

I train year-round, which means ambient summer temps in the 100s and a temperature-heat index without shade of 115F or higher, with dewpoints around 68-72 on a good day. Mind you, I’m not complaining. It’s way worse in south Texas!

This article shares what I’ve learned as an ultrarunner with Type 1 diabetes training and running in this environment.

Heat = stress = possible high BG = problems

Heat causes stress. Stress will make your blood sugar go up: I blogged about stress previously. Add to that things like dehydration and you’ve got a recipe for potential diabetic disaster.

The heat index is based on what it feels like…in the SHADE.

The heat index is what the temperature feels like when you combine the actual air temperature with the amount of moisture in the air. And that air temperature is measured in shade, not direct sunlight.

Yesterday the heat index here was 110°. So really, in direct sunlight it was more like 125° .

This seems to be widely unknown, but that’s indeed how it works. Here’s the official chart (see the explanation about shady conditions at the bottom). You can also read more about this here.

So 90 degrees in the shade and 75% relative humidity “feels like” 109.

But direct sunlight increases the “feels like” temperature by around 15 degrees.

So now you’re looking at about 125 degrees, not “just” 109.

Oh, and strong winds make heat even more hazardous. You feel deceptively cooler, but in reality your environment is still smoking hot.

For real.

Asphalt pavement is usually 130-140 degrees.

If you’re running on asphalt, both the air temperature and the “feels like” temperature are even hotter. Figure on pavement temperatures around 130-140 degrees during the hottest summer months. Concrete runs about 10 degrees cooler than that.

I have literally run on asphalt so hot that it was soft, melting and sticking to my shoes in huge clumps of melted pavement and gravel. Unbelievable.

One workaround is to look for grass, gravel or sandy shoulders so you can minimize your exposure to this kind of heat.

I also strongly encourage changing sweaty and/or dirty socks and taping your feet, because heat like this makes skin breakdown and major blisters even likelier.

Insulin breaks down above 90 degrees.

I see questions all the time on Facebook: “Does heat really mess up my insulin?” Often, the most common answer is “Nah, it never caused me any problems, you should be fine.”

The truth is that some of these folks probably did experience cooked insulin but blamed the resulting high sugars on hidden carbs or vacation enthusiasm in restaurants. They probably believed the myth that clear insulin is always good.

But the truth is that you can’t tell by looking if insulin is cooked. Not all cooked insulin is cloudy, at least not right away. Plus, once it starts breaking down, it gets less and less effective as time passes. It’s not an on/off switch, where one day it’s working and the next day it isn’t.

I’ve had three different episodes of cooked insulin in the summers of 2019 and 2020. Was it hotter those years? No.

I think what changed is that now I’m using the Tandem pump which has a 300-unit reservoir. My old Animas pump only held 200 units. My TDD is about 30 units on a rest day–on running days more like 20. So my Tandem insulin is exposed to heat for 10 days, vs about 6 days for the Animas.

And for the record: once the insulin was cloudy. Twice it was still clear.

Fortunately, we don’t have to guess at the effect of heat on insulin. The effect of prolonged heat exposure on insulin was answered by a 2009 study.

The bottom line: Humulin insulin potency dropped by at least 15% when stored above 90 degrees. Other varieties probably don’t differ much in heat resistance.

Who knows what happens when it’s above 100 degrees and you’re out in it all day, often with your insulin pump in direct sunlight?

Nothing good, that’s for sure. Pretty sure the insulin’s going to break down even faster.

For me, the telltale sign of cooked insulin is when correction boluses are about as effective as injecting water. If you’re trying to convince yourself that for some reason that bowl of keto cereal and Fairlife low-carb milk suddenly spiked your sugar after several days of long hot runs…try correcting with a fresh bottle of insulin.

Looking at the T:connect data upload is also useful. The changing BG trend and TDD vs normal days with good insulin are easy to see. And the insulin-on-board overlay is an instant visual shock of just how much extra insulin it’s taking to make even a tiny dent in it.

I’ll also start to see ketones when I test with my ketone meter.

When that happens, I do my next adjustment with a syringe and a fresh bottle from my fridge. I’ll also unplug my pump and shoot the same number of units into the air, so my IOB calculation is still accurate.

If the adjustment works, I swallow hard and discard the insulin in my pump. Ka-ching.

Here’s what I’m doing to prevent this going forward:

I get separation anxiety when I don’t have a bottle of insulin in my pocket and I dragged my feet on changing that. But I’ve learned the hard way to leave the bottle itself at home or in the Frio case if we’re on the road in hot weather.

For the insulin in the pump reservoir, I have a Frio pump wallet. I use that on runs, but on long daily walks with my wife, I just stick a cold water bottle in my pocket and tuck my pump in alongside.

Control-IQ update

I upgraded to Control-IQ and its automatic corrections in the Spring of 2020, about halfway through my run across the US, during a COVID pause. As a result, I don’t usually do many manual adjustments. I just let Control-IQ do its thing. Recently, I had a couple days of high-ish sugars. Since I wasn’t manually adjusting much, I didn’t notice right away just how much my TDD had gone up. When I realized it was about 30% higher than usually AND I was still running high, I did my next correction bolus with a syringe and fresh bottle. BOOM! That was it.

Lesson learned: Don’t let Control-IQ lull you into taking your eye off that TDD ball if you’re running high. In this case the whole bottle was a dud even though it had been in the fridge, but it just as easily could have been cooked insulin in my pump cartridge.

You are a heat sink.

No matter how hot you feel, your body is probably still the coolest thing out there.

When the air temperature is hotter than about 98.6, your body acts as a heat sink. It soaks up heat from the surrounding, hotter air.

Noon is not the hottest part of the day.

Yes, the sun is right over your head. But it takes time for that heat to travel to Earth.

The hottest part of the day in summer is usually 3-6 PM.

That’s why my most-used phone apps are the Weather Channel app and the Dark Sky app.

Getting a sense of the tempo of the weather in each season—when it’s hottest, coolest, least and most humid, when first light and last light fall, the relationship between barometric pressure and rain—has been incredibly useful as I’ve run longer and longer distances.

Dew point, not humidity, matters.

We all talk about humidity. What actually makes it miserable to run is a high dew point. Here’s a good explanation of the difference between relative humidity and dew point.

A high dew point means that the air is already full of moisture and stays that way as the temperature rises. That makes it hard for your sweat to evaporate—there’s nowhere for it to go—which means you can’t cool down as much.

If you train consistently in hot, humid weather with a dew point in the 60s, it’s actually pretty bearable, even though most of the non-heat-acclimated folks around you will complain about it.

But hot weather with a dew point in the low 70s will always be sheer misery. And a dew point 75 or higher, plus temps above 90, is getting into “unsafe to run even if you’re heat-trained” territory.

Hydration doesn’t prevent heat stroke.

Yes, you need to “drink to thirst”, for sure.

But even well-hydrated people can get overheated.

Don’t confuse dehydration with a heat illness. They are related, and proper hydration helps avoid heat illness, but they are not the same.

If you’ve stopped sweating, have a headache, can’t think straight, feel lightheaded, etc., you need to stop exerting yourself and cool down.

Be aware that once you’ve had heat exhaustion or heat stroke, you’re likelier to have it again.

Electrolytes, right?

The science on this seems inconclusive. For what it’s worth, here’s what I do. YMMV.

I drink water.

I also drink Gatorade G2. I like the idea of a “basal” level of carbs, too.

I also like the G2 electrolytes, but not for the usual reasons runners give.

One thing I learned after an ER trip is that very low blood sugars can cause dangerously low potassium levels. Low potassium = heart arrhythmias = the likely cause of “dead in bed” among T1s.

I’ve had some pretty tough lows on occasion, so I like the idea of topping off my potassium levels when I know I am sweating out some of it.

And when I do all-day runs and rides in the summer, sometimes I’ll take an S-cap every hour if I think I need it.

My rule of thumb for “Do I need electrolytes” is based on how the G2 tastes. If it tastes sweet, I figure my body needs the extra electrolytes. If it tastes salty, I figure my own electrolytes are doing fine and I’ll go with water and skip the S-caps.

I also like the “drink to thirst” idea, so I do that vs focusing on drinking a predetermined amount.

My mind can play tricks on me, though. I’ve noticed that on super-long events like my run across Texas, even though I know Leslie’s not far ahead with our van and we have lots of liquids, if I can’t see her, I find myself subconsciously rationing my water.

Dumb, right? Don’t do that.

Heat makes your heart rate go up.

I’ve seen articles for Runners World and similar sites that talk about pretty small heart rate increases. The Cleveland Clinic says your heart rate goes up about 10 bpm for every degree your core temperature increases.

My own experience is that if you’re running in seriously hot temperatures, your heart rate goes up a lot more if you try to maintain your regular pace.

You just can’t do it, and you shouldn’t even try.

If you’re running ultra distances, you already know that ultra doesn’t usually happen at a marathon pace. Neither does training in really hot weather.

Expect to slow way, way down.

Heat training takes time, but it lasts.

The big advantage of heat training is that it slows the rise in core temperature and heart rate, trains you to sweat earlier and more while losing less sodium, increases blood flow to the skin, and reduces the amount of heat your body itself produces. All of these things help keep you cooler and protect against heat illness.

The Army has done a ton of research on how to help people quickly adjust to extreme heat and humidity. You can peruse the official Ranger & Airborne School’s Heat Acclimation Guide here.

The bottom line is that it takes at least 2-3 weeks of daily heat exposure totaling about two hours/day. Ideally, the heat exposure should be paired with cardiovascular exercise, like power walking or jogging.

I compare it to boiling a frog. If you live in an area with hot summers, just keep up your outdoor running schedule as local temps increase in the spring and into the summer. If daily runs don’t make sense for you, get out and power walk, or ride your bike hard.

Now, if you live in Denver and still have snow on the ground in June and you’re planning to do an event in New Orleans in July, I strongly recommend starting sauna training many months before your event, not weeks.

How long does heat acclimation last? The Army says you lose most of it after about three weeks if you’re not getting consistent heat exposure.

My experience has been a little different. Between the sauna and Texas weather, I heat-train year-round. What I’ve found is that I retain most of my heat acclimation even if I skip a few months.

Dry and steam saunas are great places to heat-train.

For reasons not yet known, an association exists between impaired heat tolerance and Type 1 diabetes. My outdoor runs, rides, etc. would basically grind to a halt by mid-June and I wouldn’t be able to restart until October.

This was a problem. I wanted to do a 70.3 and 140.6 Ironman. I wanted to ride Austin’s double-century Tour de Cure. I wanted to run the 223-mile Capital to Coast relay solo in October. I wanted to run the Honey Badger 100 mile road race in July. I wanted to run across Iowa in June. I wanted to run across the U.S.

I had to be able to train and keep moving in the heat.

The answer: sauna training. I do both dry and steam sauna, so I get both hot desert and humidity training. I just sit. I don’t exercise or stretch in the sauna, although some people do. I drink plenty.

I also make effort to preserve body temperature by keeping my arms and legs close.you might think that would maske you feel hotter, but it actually exposes you to less heat. And for me, at least, sauna is not about seeing how much heat I can stand, but about seeing how long I can stand it. That means minimizing the suffering, not maximizing it. There’s a subtle difference.

I’m up to about 45 minutes in the dry sauna, about 35 in the steam sauna.

It’s been a game-changer for me.

If you don’t have sauna access, one alternative is to run on an indoor treadmill where you can crank up the furnace.

I’ve had to give up my gym membership and sauna access due to the virus, so I’m working out in a hot room, doing heavy yard work in the middle of the afternoon, and doing all-day training runs consistently. It all helps.

Another option is to layer up with more clothes for your heat training runs than the outdoor temperature demands. Instead of automatically switching to cooler and cooler clothes as the spring and summer temps rise, wear extra layers, long-sleeved shirts, running tights vs shorts, and so on.

Then, for your actual event, remember:

Covering your body keeps you less hot.

I won’t say cooler, because you will not be cool. It is hot. You will be hot.

But studies have shown that in hot weather, running shirtless or in a tank top drags down exercise performance because it exposes you to much more heat.

Wearing a lightweight technical shirt with sleeves keeps the worst of the sun off you. Not just short sleeves. Long sleeves.

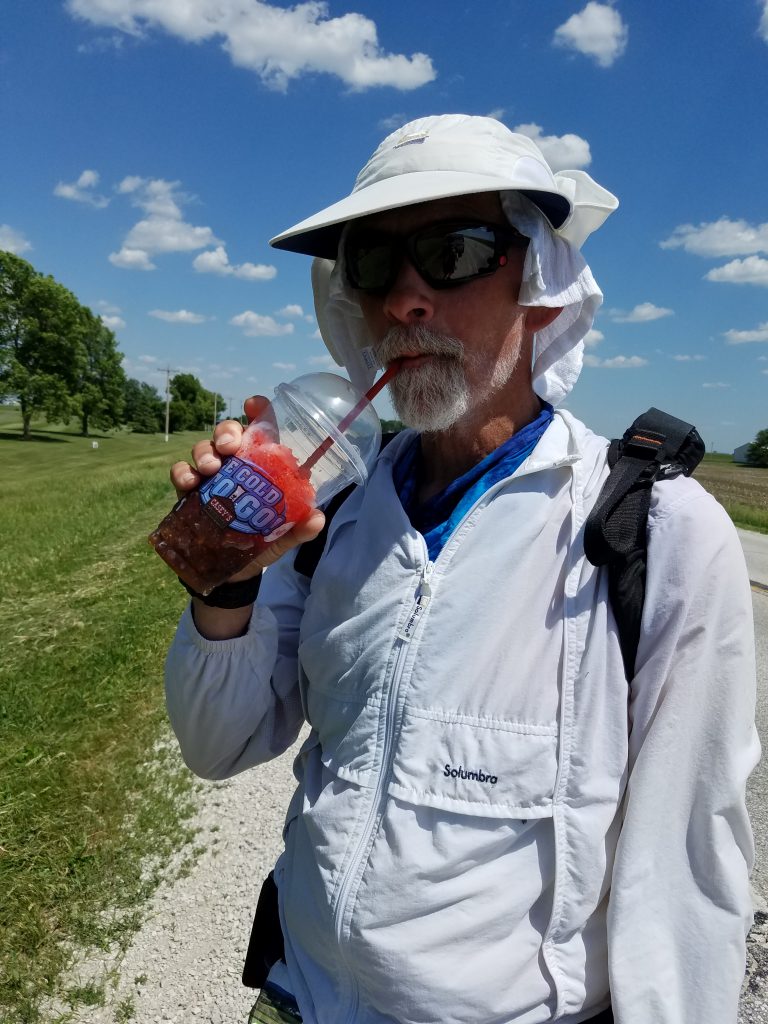

Something like Solumbra’s ultra runner shirt or even a super-thin cotton dress shirt is the way to go. Solumbra’s desert running shirt is made from very thin technical nylon fabric, vented for maximum sweat evaporation and cooling.

Solumbra also has vented long loose pants made from the same material.

The design incorporates a “heat chimney” similar to Touareg robes in North Africa. It helps route heat up and out when temperatures are above body temperature and evaporation thus no longer works.

Leg and arm cookers can also help.

But I have a love/hate relationship with DeSoto Sports leg coolers.

The part I love: these are technical, highly wicking, thin leg sleeves that cover you from mid-thigh to ankle. They’ve got spandex or something like that, so they’re form-fitting, but they’re not compressive.

The part I really hate: they have a narrow silicone band around the thigh that helps them stay up. It rubs my legs raw, literally to the point of bleeding, within just 2-3 days of running. I still use them, but i have found that Iconic del Sol leg coolers, which use a layered Spandex hem, don’t rub my legs raw. Guys, if you can find the plain white ones, they’re great. Don’t be flustered by the lady in the picture iwearing them.

Pick the right hat.

In cooler weather, I love my lightweight running caps.

But I figured out a couple years ago that they weren’t the answer for really long hot runs in direct sunlight. No airspace between your head and the top of the hat’s crown. No real ventilation. The bill’s too small to protect you from constant glare in shadeless environments like the Mojave. Your neck and the back of your head just get cooked All.The.Damn.Day.

You need to take your cues from landscaping crews in hot climates.

Your hat needs to let a lot of air pass through. It needs some space between the top of your head and the crown of the hat. It needs a really big brim, all around, to keep the sun off you. And it needs a Kalahari neck flap to protect the back of your head and neck.

This year I added a new Shelta desert hat model that I’m liking even better than the Solumbra hat I wore for several years. They sent me a high-vis one that’s great for road running and I have a light khaki color that I wear for training.

Are Shelta hats worth it? Yes. These hats are awesome. Super-featherweight fabric so the neck flap provides both coverage and ventilation, like below, room for air to move across the top of your head underneath the hat’s crown, plus excellent wicking and evaporation. So far it has never blown off even though a lot of days the winds here gust 30-50 mph. I’ve used the cord to make sure it didn’t blow off on a bridge a few times when it was really windy, but it pretty much stays put anyway.

I’ve also got a Raidlight and an Outdoor Research hat that were early experiments and still see some use, and I’ve also seen folks wear oversized straw hats.

Leg and arm sleeves are weird and wonderful.

I talked about these a moment ago. so let me explain. You wear cooling sleeves and leggings both to keep cool and to keep road grit from sanding down your skin.

Heat has 3 components: radiative, convective, and conductive.

When youfeel a breeze, that’s convective heat loss. But without a UV-reflective skin covering, your body will heat up from the radiative component of sunlight, no matter how much sweat and evaporation help.

Sleeves also cool you in the same way canteens keep water cool: they create a conductive path for heat loss that is fed by evaporation at the fabric surface. That’s wicking. But your favorite summer-weight running shirt probably isn’t long-sleeved, unless you’re used to running in the desert and have discovered Solumbra shirts.

Some sleeves are also impregnated with xylitol, which gives your skin that same minty-fresh feeling you get from some chewing gums. You can pre-wet the sleeves and leggings before you get hot and you will feel cooler.

Now, cover your body when you are out in the heat and people will give you sidelong glances and avoid you when you drop by the convenience store during your run to get more water. But when you’re running on exposed pavement, no shade in sight, white cooling sleeves are hugely helpful, and they’re great at preventing windburn if you’re dealing with both sun and 40-50 mph winds all day long (West Texas oilfield country, I’m looking at you).

Ice can keep you going.

I’m not a fan of ice inside hats, although I’ve seen hats made for this purpose. I don’t want the weight on my head. The ice melts super-fast. Then it runs down my shirt, feels more wet than cool, and soaks off my insulin pump infuser and continuous blood-glucose monitoring (CGMS) sensor no matter how much SkinTac I use. That’s the last thing I want to deal with.

What works better for me: periodically soak a small sponge or transition towel in ice water. Just flop it down over your head, wrap it around your neck. You can squeeze it out over your head if you like that.

I also like the ice bandanas I got from Zombie Runner when they still sold running gear. Their Cool Off Bandana has slots for ice, plus a sewn-in chamois that holds moisture as the ice melts. I still like to put my ice in snack-sized baggies before I slide it into the bandana so it doesn’t soak my shirt and loosen my infuser and CGMS sensor.

The other reason I don’t like lots of ice melt is that it runs down into my shoes and soaks my socks. Tons of moisture + feet + heat = rapid skin breakdown. Not good.

Hold icy water bottles against your carotids & back of your neck.

Does it really cool down your core temp or your brain? Who knows?

But it feels good and always picks me up when I’m feeling parboiled.

You can also press icy cold bottles under your armpits and in the groin area. Large blood vessels are near the skin in these areas, so it helps cool you down faster.

Plunge your hands and wrists in ice water.

This is one of my last-resort strategies. Surprisingly effective.

Cooling slushies. Maybe.

Some research has suggested that drinking a slushie before a hot workout improves your heat tolerance. And for sure some ultrarunners swear by eating chunks of ice in hot conditions.

Hard to say whether it’s a placebo effect or not.

On my ultra events across the USA, Texas, Iowa, etc., I’ve drunk a ton of icy liquids, although I don’t usually do the slushie thing methodically. I have had a couple of slushies (with real Coke!) mid-run that were delicious. And for sure icy liquids made me feel better momentarily.

Your mileage may vary.

Ice vests or other cooling vests?

Don’t know. Looked into them. Wasn’t persuaded. Now I see they’re using custom ice vests to pre-cool athletes at the Tokyo Olympics anytime they’re not actually competing.

My closest experience with something similar: I’ve run with Camelbaks that I froze overnight. The cooling effect was temporary. After that, I just felt like I was running with a big bag of warm water on my back that prevented me from venting heat.

I also didn’t like the idea of running with the extra weight of the vest itself, plus the ice, in super-hot temperatures.

Hydration packs?

Been there, done that. See above.

I’ve looked at quite a few other “ultra vests” but they usually assume you want to carry bottles in the front, often as an adjunct to a bladder on your back. This strikes me as the worst of both worlds: weight distribution that tends to pull you forward, plus skunky, leaky hydration bladders.

Walk the sun, run the shade?

If you train or race in areas with only intermittent shade, you’ll find yourself engaged in a constant internal debate:

Run the sunny part, so you can then slow down and benefit from the shade?

Or walk the sunny part, and run while you’ve got shade that lessens the physical demand on your body?

I usually run the sun and walk the shade.

But really, there’s no right answer.

The real key is to pick the one that works best for you, so you can establish a tempo that maximizes the tiny bit of recovery available to your body in these tough conditions.

Don’t fall into the trap of running the sun to get out of it fast, then running the shade because it feels better. It’s hot. You need to walk some. If not, eventually the heat will catch up with you and you will be walking everything, very slowly, overheated, dehydrated, and half-delirious.

Run early or late?

You can’t run only during your favorite parts of the day.

If you want to train for extreme ultra distances, I think it’s wise to both heat-train and train to run overnight, when it’s cooler. You’re going to need to do both at some point.

For multi-day ultra events, some folks believe it’s better to take a siesta during the hottest hours. They like to run overnight, when it’s cooler.

That is not me. I wanted to be that person. And I tried.

But I have a hard time resting during the day.

And I really hate running late at night. My mind goes to bad places.

I love running at sunrise and sunset.

So these days, I keep going during the afternoon, but I cut myself slack when the temperatures are brutal. And I run overnight only when it’s unavoidable.

You do you.

Prescription sunglasses: worth it.

My progressive bifocal Oakleys with Transitions are probably the single most expensive piece of running and cycling gear I own. Yep, more than my bike, because I ride a 10-year old aluminum Specialized that I bought used at my LBS.

Here in Plano we’re lucky to have ADS Sports Eyewear, owned and operated by another guy with Type 1 diabetes, and that’s where I got mine. They’re not the same as the tres stylish Oakleys you see in their store at the mall. In fact, I almost didn’t get them because I thought Oakley was just a fashion brand these days.

Now that I’ve had them for several years, I wouldn’t trade them for anything except maybe a cure for diabetes.

Most of my training routes don’t have much shade, and the glare is just relentless on all-day runs in the summer. I love the Oakleys because I can wear them from the crack of dawn into night, thanks to the photosensitive coating. Unlike old-school versions, it really does turn completely clear when no UV rays are present.

The full-jacket design keeps crud out of my eyes, which is a big deal for road running where cars and trucks zoom past at 70+ mph and constantly kick up dust and gravel and all kinds of stuff. The only downside is that despite tiny vents, sometimes they mist up a bit if I stand still in really humid temps.

Heat stress raises blood sugar.

The physiological stress of running in really hot weather can raise blood sugar significantly in my experience.

I had a lot to say about the effects of physiological stress on blood sugar in people with Type 1 diabetes here.

But before you assume persistent highs are stress-related, make sure your insulin’s still good.

Remember to eat anyway.

For whatever reason, many of us aren’t very hungry when it’s really hot.

But if you’re running long distances, and you’re Type 1, you definitely still have to eat.

Plus, food isn’t just calories. It’s also a significant source of water in your daily diet.

The thing about eating is that your body needs food and energy both to run, to minimize unwanted muscle breakdown, and to recover. If you’re doing only occasional runs, or pretty short ones, it’s not such a big deal.

But if you’re doing ultra-endurance, where you’re out there day after day after day, food, and enough of it, is critical.

Remember to test.

I have a headache. I’m drenched in sweat. My heart is racing. My running stride is floppy. My energy has vanished. I can’t remember how far it is to the next marker. I can’t think straight.

Overheated, or low blood sugar?

Time to find some shade…and test.

Because it could be both.

Run on!