Your donations help T1Determined #keepgoing.

What It’s Like Out There: Running Across The United States

I’ve done five different ultra runs, starting with the 100-mile Honey Badger road race and then Capital to Coast solo at 223 miles, Relay Iowa solo for 339, 2019’s FKT (Fastest Known Time) across Texas for 850 miles, and most recently, 2748 across the US, including the first ever run from Disneyland to Walt Disney World.

I’ve gotten a lot of questions about what it’s like to run these distances.

Some are practical: “You don’t actually run every mile, right?” or “You don’t really run from sunup to sundown, do you?”

And some are philosophical: “Doesn’t it get boring? What do you think about all day?”

The answers differ slightly depending on whether there are cutoffs, finish-line clocks, or whether the run’s long enough to include rest days. Every one of those affects your training, your mindset, and how you run your race.

But setting that minutiae aside, here’s what it’s like for me out there: the nuts and bolts, the day-to-day slog, the games your mind plays at the point of exhaustion, and the exhilarating highs of what can become a profoundly transcendent journey.

Nuts & bolts

Run. Eat. Sleep. Repeat.

My days are simple: Run. Eat. Sleep. Repeat.

I’m up before dawn so I have time to get ready and if necessary drive to the previous day’s end-point which has turned into today’s start-point. Before I head out, I eat a small breakfast of carbs and protein, usually breakfast cereal in a cup with a whey shake. Experience has taught me not to load up too much on carbs, because they just spike my blood sugar and then it’s hard to fuel for the rest of the day.

My plan is generally to spend every hour of daylight running, so I usually start running at sunrise, or at first light if I’m trying to squeeze in extra miles. I know some folks love the cool and quiet of night running, but I worry about tripping, and to be honest my mind goes to dark places at 3 a.m. in the middle of nowhere. Not worth it.

I aim for a daily goal of 30-35 miles, very occasionally 40 miles. If it’s blistering hot, rainy, or I’m working around a physical issue like an imminent blister, it’s a little less. I know that’s nothing compared to putting 100 miles without sleep (which I’ve done before), but after my first 200-mile run, 65-mile-a-day grinds, and only getting 7 hours of sleep in 3 and a half days, the hallucinations showed me I wasn’t superhuman, and if I was planning on doing this Every Single Day, I’d have to cut back a bit for a USA run. After serious back and ankle injuries on my FKT across Texas, I was sure I needed to cut back. So I did.

I run at a typical ultra pace. Best case it’s about 12 minutes/mile, most days it’s about 15, and when it’s 90-100+ degrees, I slow down to more like 17-18 minutes/mile. If the bone spur in my foot is acting up, my sugar’s high or I’m dehydrated, I’ll slow down. (Believe it or not, the spur’s from a swimming injury.)

Each day’s eleven hours or so of running are interrupted by restroom stops and fuel breaks. That’s on purpose. I know I can eat running, or walking for that matter, but I’ve found that time off feet actually needs to be part of my strategy if I want to avoid foot injuries that could take me off my run for several days. On a transcon, you don’t have the luxury of going all out and then crashing with a handful of aspirin, lidocaine cream, and a 14-hour nap.

I usually eat about every 60-90 minutes, or around 8-10 times during my actual running day. My longest breaks are usually about 20 minutes for lunch and if the run is longer than about 35 miles, again for supper. Most food breaks include a protein shake, and if it’s chilly, Leslie usually fires up the camp stove and makes something hot. Otherwise, everything’s room-temperature, like cookies or peanut butter; or chilled, like hummus, egg salad or string cheese. I try to eat about 4000-5000 calories/day, I’ve learned that my body will burn whatever fuel’s available, and if I don’t feed it, that’s fat and muscle. Most ultra runners don’t really need to lose fat; and when muscle is metabolized, capillary permeability increases to get rid of the byproducts, and my already- hyperactive immune system goes ape-shit over all the unrecognizable stuff floating around in my bloodstream. That puts me on the edge of rhabdo, and that’s not a good thing.

I’ve had people ask me why I don’t just use runner’s gels or Tailwind or UCAN instead of real food. It comes down to these three things: 1) I need protein, fat and calories, not just carbs, 2) at longer distances, I run at a slower pace and higher-protein/higher-fat food seems to last longer, and 3) I just like real food better. You’ll get sick quickly of eating “ingredients” instead of real food. That last one shouldn’t be underestimated. Relying strictly on gels or Clif bars for 50-100 miles is bad enough. Eating them non-stop day after day is downright repulsive.

My wife and crew chief Leslie and I are constantly calibrating what I eat to what my sugar is doing, and weighing whether to manually adjust or let Control-IQ do its thing; but I also have to remain open to the possibility that I’ve got a bad infusion site, or that my insulin’s cooked, all of which takes time and can be a bit like solving a whodunit while balancing spinning plates on the end of long sticks.

When I’m high, the challenge is to make myself dose enough to lower my blood glucose (BG) so I can actually convert the sugar I have on board to energy. I’ve learned from experience that you can’t just skip carbs and try to run a really high blood sugar down. You have to dose it down, and eat carbs, and keep running.

On days when my sugar runs persistently low, I’ll usually just swallow a 2-ounce glucose “shot” because that kicks in way faster than food, test a lot, and wait if I have to for my blood sugar to come back up. No matter what the day’s mileage goal is and no matter how desperately I want to get moving again, I literally can’t safely go until I get my sugar up—and that’s a very important point to remember if you’re Type 1 and trying something physically difficult. A good day is one where you wake up the next morning.

During food breaks, I also check my progress against the planned route, check “hot spots” (pre-blisters) on my feet, apply Chapstick to wind-chapped lips, treat heat rash, clean road crud out of my socks and shoes (it still gets in despite gaiters), test my sugar, and sometimes change my insulin pump infuser or Dexcom CGMS sensor if the numbers aren’t cooperating.

People laugh when I say I just run, and Leslie does everything else. She navigates the preplanned route. She arranges our overnight stays several days in advance. She keeps an eye on the Garmin tracker and the deep-cycle battery and fridge setup, troubleshoots unforeseen issues like weather delays or road closures, finds safe spots for meal breaks and keeps a constant flow of food & liquid going. She helps me figure out what to do about prolonged highs or lows, and anticipates what I’m likely to need next.

Someone once asked how I could run all day and still be active on Facebook and do media interviews. Again, that’s Leslie. During the run, she handles all the email and social media and coordinates meetups with followers, local papers and TV stations.

I meant it when I said I just run, eat, sleep and repeat. I’m extremely single-minded about getting a fast shower and going to sleep as fast as I can. I hop in the van and we head straight to wherever we’re staying, usually eating in the van on the way. Once we reach our accommodations, I scan the next day’s route and weather, prep accordingly and charge my insulin pump.

At most, the two of us generally have 1 free hour.

If all goes as planned, I’m asleep by 8:30 PM, 9:30 at the latest. I was able to skimp or outright skip sleep when I ran the shorter Honey Badger and Capital to Coast routes, but I knew it was completely unsustainable for Iowa, Texas, or the US–and a generally bad idea–when after that 223-miler, I couldn’t think straight, imagined anthills were guardrails, and was seeing multiple copies of my crew members at the finish line.

All of this stuff, the running and everything else, I just do over and over and over, all day long. It doesn’t take many consecutive days of this to start frying your brain.

Dressing for success

When I first did my run across Texas, some people asked me why I wore a huge boonie hat, a neck buff, and a long-sleeved white shirt plus a waistpack and water vest, especially since the van’s never far away. I’m surprised no one asked about the diaper paste I put on my lips.

The short answer is that all these things either protect me from the elements or forestall unexpected problems, and on any given day, you don’t know what those problems are going to be.

The desert shirt is UV-reflective and vented, with cinched wrists that force warm air out of the neck to cool me down. It also protects against the blowing sand that’s common in west Texas (strangely, not the Mojave). The boonie hat keeps the sun off my face and neck. The diaper paste prevents and heals wind-chapped lips. The neck buff keeps sun off my neck, dust out of my face, and works as a half-assed COVID face covering in an emergency if I double it up. The water vest keeps me hydrated when 3-mile water stops at the van aren’t enough, and it also holds my GPS beacon and eyeglasses case. The waist pack holds my cell phone, glucose tabs, glucose meter and lancing device, ID, phone, and a small flashlight for reading turn-by-turn directions at dawn and dusk, when I also wear an LED light vest visible from at least a mile away. Gaiters keep cockleburs out of my shoes.

I’ve tried running across states without this stuff. I’ve been told it makes me look like a Jamaican cop. I don’t care. If it’s supposed to an insult, I refuse to take it that way. Everything is here for a reason.

If you’re overheated, sunburned, or your shoes are full of road grit and cockleburs, don’t say I didn’t warn you.

Caution: road hazards

A big part of my day is just getting safely from Point A to Point B, in one piece.

I typically plan routes around flat, smooth roads with wide shoulders and low traffic but of course the reality is still lots of narrow or absent shoulders, cambered (side-slanted) roads, potholes and drop-offs, rickety narrow bridges, traffic, knee-high thorny weeds and cockleburs. Not to mention drivers looking at their phones. I see a lot of that. One in eastern Arkansas actually wrecked their car after swerving to avoid me when they drifted off onto the same shoulder I was running on.

It comes down to picking the safest roads available, then dealing with what’s left: does that patch of weeds look safe to run through or should I just stop moving altogether until that wide-load trailer passes by? Uh-oh, that’s not dirt, that’s a giant ant colony! Can I make it across this bridge before those cars about a mile away get to it?

Roads without shoulders make me most anxious, but sometimes they’re the only choice. Most of central Alabama was that way. You have to stay constantly alert and ready to take action if a driver does something unexpected, even though every day you’re more physically and mentally fatigued than the day before. And your choices are limited: steep drops and six-inch shoulders covered with slippery pine needles. I get out my trail running shoes for that.

Many roads and shoulders are cambered—the edges slant down several inches so rain flows off them. Since human legs aren’t cambered, running on roads like these for hundreds of miles can really mess up your ankles, knees, hips and even discs in your back. Ask me how I know.

When I’m training, I do strength and balance workouts that help a good bit. During runs, I try to avoid camber, either by running on flat shoulder if it’s available, or by running closer to the center of the lane—but that takes even more attention since I have to be ready to bail for a safer spot at a moment’s notice. No matter what, there’s always a trade-off: cambered pavement, muddy shoulders, tall weeds, stripped tire retreads, holes, road debris, and a bunch of other stuff you can hardly imagine.

Perhaps the most unexpected hazard is litter. Human beings in the United States seem to litter as easily as they breathe: from fast food trash, discarded bras, construction helmets, tools, instruction manuals and all kinds and manner of garbage, to entire cartons of roofing nails, broken glass, barbed wire, and vicious metal threads from blown tires and lost retreads.

I absolutely shredded my palm in Coolidge, AZ when I got tangled up in loose wire on a bridge and grabbed a sharp guardrail to avoid falling into traffic.

“Who’s a good boy? You are, yes you are!”

Normally, I love dogs. But other than traffic, my single biggest concern is probably loose dogs, especially in unincorporated residential areas.

Most dogs are just curious, or at worst, protective of their property line. Dogs in this category are usually at least a little domesticated. As long as I slow to a walk and stay on the other side of the road, they generally limit themselves to barking. If they approach fast, even running across the road, and seem more perturbed, I’ll toss a treat as far away from me as possible, and waving arms with my big floppy boonie hat at them and yelling “Stay!” usually works really well if they keep coming.

In areas with lots of loose dogs, I use a bright blue collapsible mini umbrella. It’s highly visible to dogs, and if you aim the umbrella at the dog and open and shut it rapidly, they often to freak out and back up. It also puts some distance between you and the dog and it gives you something to ward them off with.

The closest call I’ve had was on US-82 outside Texarkana, TX during my Texas run. Leslie had texted me with a heads-up about two large, feral dogs—but when she checked the areas a second time, they had vanished, so she headed on up the road. They circled me, getting closer and closer, and didn’t give a damn about my hat-waving, yelling and umbrella.

Fortunately a guy in a big pickup truck was driving past, realized what was happening, and drove onto the shoulder between the dogs and me. They ran off into the woods and I started moving fast. My Good Samaritan just waved, and drove off.

I don’t use pepper spray. It’s a good way to make a dog so angry it will rather kill you than give up fighting. I am, however, considering a mini stun gun, just because the noise is said to be a pretty good deterrent.

The dogs I’ll remember forever, though, are the heartbreakers: the friendly, loving strays who’ll run half a dozen miles with you just because. Cookie, Dogales, and Bodie, I’m looking at all of you.

Dust in the wind

Every season is dust season when you cross through the Mojave, Sonoran and Chihuahuan deserts in California, Arizona, New Mexico and Texas. At some point your legs, arms and face are going to get sandblasted by 40-50 mph gusts, and even on a cold day, the sun can be unrelenting.

It only takes a couple of days of sun and wind for your lips to become cracked and bleeding. When a neck gaiter, Chapstick and Vaseline don’t help, I put industrial-strength diaper paste like Desitin Max or Boudreaux’s Butt Paste on my lips. It looks gross, but it’s thick, full of zinc, and it works.

I nearly always have my arms covered, either with a long-sleeved shirt or arm sleeves. Everything’s always blaze orange or, second-best, hi-vis yellow. I want to be seen, I don’t care if I look like a human safety cone.

Here comes that rainy day feeling again

Unless it’s dangerous, I run in the weather I get. I won’t do thunderstorms or tornado warnings (learned that in Iowa). Outside of that, I depend on rain gear: specifically, a waterproof hi-vis jacket and water-resistant pants.

The biggest problem with rain is soaked shoes. My so-called “dew gaiters” keep water out of my shoes in wet grass. But actual rain gets into your shoes no matter what. It just does. Then you’re running in wet socks and you have to wait out the rain and change socks and shoes, or run until you get macerated, waterlogged skin that blisters, breaks down and presents an infection risk.

I pack dry backup shoes and fresh socks in the van, and force myself to take the time to change once the rain lets up.

For the record books

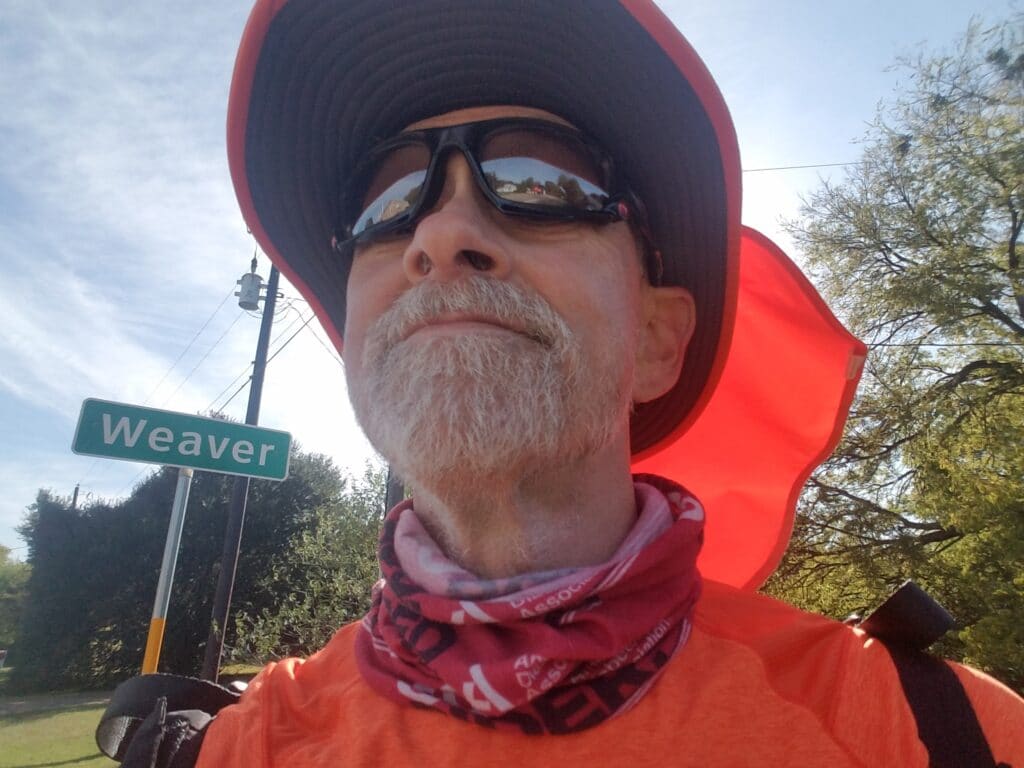

Sometimes folks ask about the selfies with street signs I sometimes post. One person even asked how I could be so vain.

There’s a reason I take those, and it’s not because I think I’m beautiful.

In addition to official world recordkeepers like the IAAF (now “World Athletics”) and famous organizations like Guinness, the “fastest known time” (FKT) community keeps track of the fastest-known-times to complete a huge number of trail and road routes around the world, from the 9-mile Blue Heron Trail in MA to the 2190-mile Appalachian Trail.

To submit a claim for the fastest-known time across Texas, I had to provide proof that I really covered every mile of it. Selfies with local landmarks, like county and city limit signs or unique local points of interest, are part of the evidence, along with the track from my Garmin InReach GPS beacon and the workout tracks from my watches (I wear two, a Garmin Fenix 6x Pro Solar and an older Suunto, on most of my super-long runs in case one fails to record). Google Photos usually records the location and time on each selfie, so it’s not hard to establish time and place consistent with your reported progress.

You always want multiple cross-referenceable data sources for recordkeeping. For instance, during the first half of the U.S. run, I fell on top of my Garmin tracker. It died a slow death over the next 24 hours after the battery internally disconnected from the charging wire connected to the USB port, finally expiring the next morning. Within the next day, my older Suunto stopped recording at 1000 kilometers and refused to reset or upload any data for the first 621 miles of my U.S. run. That left me with about 48 hours worth of missing data, a gap filled by my end-of-day selfies.

That said, sometimes I just have to take a picture of a sunrise, a puppy, an abandoned gas station, or a flower growing up through the asphalt.

Those are for me.

Mind (and body) games

Physical wear and tear

No matter what you do, days and weeks of running grind you down. You try to eat and sleep as much as possible just to slow the wear rate down, because there’s no way you’ll get enough calories and rest to actually recover until the run’s finally over.

I learned back in 2017 when I averaged 65 miles/day running the Capital to Coast 223-mile course solo that I had to keep my miles and my pace at a level where I can manage them. Too many miles and not enough sleep and your body breaks down. Back then, I could hardly form complete sentences by the last day and had major blisters on both feet despite lubing and taping.

The next year, when I ran 339 miles across Iowa, I planned to average 45 miles/day and at least 6 hours of sleep every night. That worked pretty well until thunderstorms slowed me down. Then I had to do 25% more daily miles on very little sleep, and my blistered feet, swollen, bruised ankles, and fragmented, one-syllable “Og-Want-Food” mindset all paid the price.

When I ran across Texas, I really did lower my daily miles to no more than 40 miles and I really did get more sleep. It made a big difference: just a couple blisters on each foot, a swollen ankle and bulged disc from road camber, and that was about it. All three of those healed on their own in a matter of a few weeks once we were back home.

Then there’s the wear-and-tear you can’t plan for, like in Coolidge, AZ, where I tripped in a loop of wire on a bridge and grabbed a sharp, dirty guardrail to avoid falling into traffic.

I’ve also gotten plenty of minor scrapes and gouges from thorns, sharp metal sign edges and other stuff you can’t even see if you’re just driving past.

So, if you see a guy out there running in orange shorts with a big rip on the butt, that’s me. Say hi.

Watching the wheels go round and round

People ask me all the time if I listen to music out here. The truth is, that’s one of the most dangerous things you can do when running roads, because while you can see approaching traffic, you can’t hear or see traffic behind you that may be changing lanes to pass someone in the lane across the street from you.

Running on roads requires constant focus. I nearly always run while facing oncoming traffic, unless there’s an exit ramp emptying onto the road. I can’t outrun that kind of traffic, and I’d rather be on the side of the road that has a nice ditch to dive into.

Add that to the crosswinds and aerodynamics of big, heavy, fast vehicles that can knock you around quite a bit and set you on edge, and you have the makings of what my Navy doc friend Terrie Wurzbacher calls sympathetic nervous system overload.

Running out here is nothing like the marathons, bike rallies and Ironman events I did where the course was closed and off-duty officers held back traffic at every intersection. It can be dangerous even when you’re trying to be safe.

I’ve learned to listen in both directions, not just look. You can generally hear a “whoosh” with a bit of Doppler shift when a vehicle approaches, and I can usually guess the size from the engine noise as it gets closer. You can even tell when someone behind you is passing another vehicle, because the Doppler pitch gets higher at the same time you hear their engine roaring. If I hear that, I don’t waste time looking. I assume it’s traffic and get the hell out of the way.

Being on high alert all day is psychologically exhausting and it can be dangerously easy to “zone out” on quiet roads. But those roads still have traffic, and very occasionally I’ve looked up to notice a vehicle swerving to the opposite lane to avoid hitting me.

That’s a not-so-subtle reminder that after consecutive days and weeks out here, my mental processes begin to slow down a bit. Any time something distracts me or demands more concentration—a change in the road surface, a loose dog, an approaching vehicle or road crossing—I make myself move to the shoulder and slow down to a walk so my brain can process the new information.

A fluid state of mind

Just outside El Paso, I saw two thorn bushes decorated like Christmas trees. In the middle of the Chihuahuan desert. In March.

Sometimes on these runs I start to get a little loopy, so I found this situation extremely, profoundly amusing. I took pictures of it and told people I was going to start photographing all my hallucinations.

My ultra running friend Rochelle Frisina, the first person to complete the Capital to Coast run solo, calls it “emotional volatility.” A singing bird or simple act of kindness can bring you to tears, and stepping in a small puddle can put you in a deep, hours-long funk that’s unproductive yet hard to pull out of. Even when you’re sleeping or taking a rest day, some of it stays with you.

Then there’s also a strange feeling you get after your run that goes well beyond a desire to be back out on the road. Wanderlust is too weak a word for it. Many of my transconner friends from the USA Crossers Facebook group say they feel unsettled after they return home. Their sleep is disturbed long after lab values for cortisol, GFR, CRP, CK and so forth return to normal. I myself have dreamed of being back out on my big run, but in the wrong state and going in the wrong direction.

Some transconners say that for months they feel like they don’t fit back in. You get edgy and anxious to be doing something that matters, even if you’re the only one it matters to.

A Quest for Tribe

Solo, not alone

Running solo, I’ve found a feeling of community over and over again, often in the most unexpected of places—like that guy in Texarkana who saved me from the aggressive dogs or another fellow I met in the Piney Woods just outside Arkansas whose uncle had died from complications of Type 1 diabetes the week I was suffering from dangerous low blood sugars in Odessa, TX.

- I remember meeting another guy on CA-111 near Palm Springs who was collecting soda cans from road litter for recycling and had used the pennies over the years to donate bicycles for over 100 kids.

- I met a real estate agent in Newport Beach who volunteered his home in lieu of a hotel, and I’ve been greeted warmly by homeless people, shared a brief celebration with a German guy bicycling west across the U.S., and chatted with a veteran riding his bike across the U.S. to raise awareness of PTSD.

- I’ve been offered a free milkshake in Weatherford and been energized and inspired throughout my runs by honks and waves after TV interviews and newspaper features.

- I’ve been prayed for by a motorcycle club in Texarkana and had a heartfelt conversation with a tough-looking guy with a knife (and a Type 1 brother) at the Howard County safety rest area near I-20 in Texas.

- Somewhere in west Texas a lady stopped and gave me an unopened, brand-new tube of Nuun electrolyte tablets (which was pretty funny since they were a sponsor and I was actually giving away Nuun tablets).

And I’ve found my T1D and T2D tribe everywhere.

- Countless meetups with other Type 1 folks, some decades younger, some older. Many doing great, some doing not so great.

- Grandparents and parents of young Type 1 kids, looking for reassurance that hopes and dreams are still possible.

- Parents of adult Type 1’s who brag on their awesome kids and their accomplishments!

- Leslie’s talked with non-diabetic spouses and partners who have never met anyone else married to someone with Type 1, and boy do they have a lot to talk about.

- We’ve shared war stories from the frontlines of lifelong, incurable chronic disease with a long-distance cyclist and “instant friend” in Arizona outside Sonoita.

- I’ve heard more stories than I can count from cashiers, hotel guests, and random strangers of losses and heartbreak and struggle from Type 1 and Type 2 diabetes, and stories of perseverance and resilience and grit, too.

- A couple, both with Type 2 diabetes, approached us in an RV park as traffic whizzed past, and formed a prayer circle for a safe journey.

- And during my Texas run, I met a guy whose Type 1 uncle died from low blood sugar at literally the same time I was struggling to survive my own episode of severe hypoglycemia hundreds of miles away.

Leslie’s not surprised anymore when people approach her at gas stations after they see “diabetes” on the van, asking if we have free or discounted insulin or diabetes meds available, and it breaks my heart that in this country of all countries, this is still even a question.

People say that America is breaking apart. But out here in the middle of nowhere, where shared humanity is all we have, I see us knitting ourselves into communities centered on kindness, shared struggle, empathy, and compassion.

Meeting God on the side of the road

When I was running from Baird through Cisco to Eastland, TX in early October 2020, I met a lady who asked me if I knew Jesus. It was hard to explain to her what it felt like, so I told her that it was impossible to run across the country and not meet God.

And yet, I wondered if our experiences were the same. Was the God of her hymnals, end-time prophecies, and closed rooms visited only on Sundays the same as mine?

I have seen the spark of divinity in the perfect beauty of the world around me, and I know why God looked at it and said it was good. I’ve seen holiness in quiet sunrises, empathy in the faces of strangers, fellowship in chance encounters, and forgiveness in accepting my own imperfections as part of my story. To me, that is God all around us. If you do not see it, you are looking right past it, perhaps for something else.

She asked me what I was running for, handed me a water bottle and $20, and prayed for healing. I told her I was grateful, wished her a blessed day, and moved on.

Heartbreak…

Back in March 2020 when COVID was just starting to become a nationwide issue, my father passed away. He had been one of my staunchest supporters when it came to running across the country, and I realized after he was gone that in part, I had been trying to make him proud.

He died three days after his 83rd birthday, from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, a condition that slowly robs you of your ability to breathe. He knew the day was coming; he just didn’t know when.

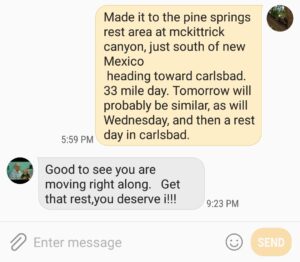

The night before he died, Leslie and I were in Carlsbad, NM for a rest day after 300 miles of running that had included 10,000 feet of elevation change as I crossed the Guadalupe Pass. I texted Dad to let him know I had made it through the pass, and his reply turned out to be the last words I would ever hear from him.

I made it okay through the drive home for the funeral, my mind swinging between grief and preoccupation with everything that had to happen once we arrived.

Then the funeral home director told us that they had to close the casket. I whispered to my dad, “Get that rest, you deserve it.” I took one last look at Dad’s face and tried to make it last as long as I could. It hit me like a gut punch that it was the last time I’d ever see him.

When we returned from the funeral, the first day of running wasn’t bad. I was mentally and emotionally wiped out, but for once physically rested.

The second day started in Halfway, NM, on a desolate road broken up by heavy trucks into fragmented pavement that looked like puzzle pieces. My pace slowed as I picked my way around potholes and cracks you could lose a small dog in, and I thought again and again of my dad. Things still felt raw, and I felt defeated. The road ahead seemed way, way too long and I didn’t know how I’d make it.

In that moment, my dad spoke to me. He told me he was proud, and had always been. He said I could do this, that he believed in me. I promised to run to his gravesite and leave him the shoes I was wearing, the ones I had run the first 1200 miles in. After a while, he said we couldn’t talk any longer, but that he’d see me at the finish line.

Now, I told you earlier about the physical and mental stress of the run, and about the emotional changes, so you can draw your own conclusions.

But to me, it felt tangible and real. It still does.

…and purpose

On March 9, 2021, after two forced COVID-related pauses and nearly a year to the day after his passing, I reached my father’s gravesite and left him the running shoes I had worn crossing the Mojave, Sonoran, and Chihuahuan Deserts.

I believe everyone who embarks on a transcontinental journey has within them a sense of purpose.

After all, if you head out there without any rhyme or reason, who knows what you’ll find or whether you’ll ever reach your real destination? And will you even know it when you see it? Is it the ocean, or something farther away, less tangible? Something that can only be found by getting back out there and going at it with your heart and soul?

For some, perhaps it’s proving to themselves or others that they can overcome obstacles that could easily have defeated them. Perhaps it’s bragging rights or setting a record. Perhaps they want to push the limits of human effort, and discover what they’re individually capable of. Perhaps they’re still searching for that elusive place, somewhere out there among strangers, that will finally feel right to them. Or driven by visceral, exhilarating curiosity to perpetually seek what’s over the next mountain.

Some months ago, I wrote about my own personal reasons for doing epic runs. Those reasons are still true, and yet I find now that my own purpose has expanded.

I’m sure the truth is that there are as many reasons for transconning as there are transconners.

I still, and always, run to show others with Type 1 diabetes that they’re not alone and they’re not powerless against this disease. That’s it’s never too late to take charge. That they can still dream big, and if they plan their training and train to their plan, nothing can stop them.

But I’m also determined now, with every single-minded, obsessive neuron in my body, to renew that promise to my dad, to get to that ever-retreating finish line having run a good race, and to see him one last time.

Then, maybe, I can finally get some rest.